For decades, Aotearoa New Zealand has traded on a powerful, pristine image—"100% Pure." Yet, as we stand at the precipice of a decisive decade for our planet, that brand is being stress-tested by the very real challenges of climate change, biodiversity loss, and resource management. The gap between our green reputation and our on-ground environmental performance is a space filled not with despair, but with profound opportunity. Advocacy for more sustainable policies is no longer a niche pursuit; it is the essential work of shaping our national destiny. This article is a call to arms and a strategic blueprint for every sustainability advocate ready to move beyond conversation and into the arena of tangible, systemic change. The future of our whenua, our moana, and our communities depends on the clarity, persistence, and sophistication of our collective voice.

The Lay of the Land: Understanding New Zealand's Unique Policy Terrain

Effective advocacy begins with a clear-eyed diagnosis of the system you seek to influence. New Zealand's environmental policy landscape is a complex tapestry woven from historical context, economic dependencies, and unique cultural frameworks. Two pillars define our current reality. First, our economy remains heavily reliant on primary industries. As of 2023, Stats NZ data shows that agriculture, forestry, and fishing collectively contributed over 5% to GDP and a staggering 60% of our goods exports. This creates a powerful political and economic constituency, often framing environmental regulation as a direct threat to national prosperity—a misconception we must expertly dismantle.

Second, and of equal importance, is the groundbreaking integration of Te Tiriti o Waitangi and mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) into environmental governance. The Resource Management Act (RMA) reforms and emerging frameworks like the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management explicitly require partnership with iwi and hapū and the consideration of Te Mana o te Wai. For advocates, this is not a box-ticking exercise; it is a foundational strength. Authentic collaboration with tangata whenua, centering concepts like kaitiakitanga (guardianship), provides a deeply rooted, values-based argument for sustainability that transcends short-term economic cycles. Understanding these two forces—the weight of agri-economics and the ascendancy of Te Ao Māori perspectives—is crucial for crafting messages that resonate across Parliament, the boardroom, and the community marae.

Future Forecast: The Trends Reshaping Aotearoa's Green Economy

The trajectory is clear: the global market is decarbonising, and capital is flowing towards sustainable enterprise. New Zealand is not immune; we are at an inflection point. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand has explicitly identified climate change as a material risk to our financial stability, signalling to banks and insurers that environmental due diligence is now a core fiduciary duty. This financial sector awakening is creating powerful leverage points for advocates.

Concurrently, a technological and entrepreneurial revolution is brewing within our primary sectors. The future of farming is not its abandonment, but its transformation—a shift from volume to value. Precision agriculture, leveraging satellite data and IoT sensors, can drastically reduce nitrogen leaching and methane emissions per unit of output. The rise of regenerative agriculture, which rebuilds soil organic matter and enhances biodiversity, is moving from fringe to mainstream, supported by consumer demand and pioneering entities like the Ahikārai programme. Furthermore, the nascent but high-potential green hydrogen industry, particularly for decarbonising heavy transport and freight, could redefine Southland's economy post-dairy. Advocates must champion these innovations, framing them not as costs but as investments in enduring competitive advantage and regional resilience.

Case Study: The Aotearoa Circle & The Finance Sector's Pivotal Shift

Problem: For years, environmental advocacy and New Zealand's finance sector operated in separate silos. The financial industry, while influential, largely viewed climate change and biodiversity loss as externalities—risks not yet reflected on balance sheets. This created a critical funding gap for sustainable initiatives and allowed high-emission business models to continue unchallenged by their capital providers.

Action: The Aotearoa Circle, a unique cross-sector CEO-led coalition, intervened to bridge this divide. In 2020, its Sustainable Finance Forum released a comprehensive roadmap with 20 detailed recommendations. The action was multifaceted: it involved direct, high-level engagement with bank CEOs, asset managers, and insurers; the development of a mandatory climate-related financial disclosure regime (now law); and the creation of practical guidance for integrating nature-based risks into lending and investment decisions.

Result: The impact has been systemic. New Zealand became one of the first countries to mandate climate risk reporting for large financial institutions. Major banks like ANZ NZ and BNZ have since launched significant sustainable finance products, with ANZ alone pledging $50 billion towards sustainable outcomes by 2030. Perhaps most tellingly, the financial sector has moved from being a passive observer to an active participant in the policy debate, now advocating for clearer government signals to de-risk their green investments.

Takeaway: This case study demonstrates that engaging the guardians of capital is a force multiplier for policy change. Advocates must speak the language of risk, return, and resilience. By aligning environmental outcomes with financial stability and long-term value creation, we can turn the entire financial system into an ally for sustainability, leveraging its immense influence to accelerate the transition.

The Great Debate: Economic Growth vs. Ecological Limits

At the heart of many policy stalemates lies a seemingly intractable debate: can we have perpetual economic growth without exceeding planetary boundaries? This tension manifests in local fights over water consents, emissions budgets, and land-use change.

Side 1: The Green Growth Optimists

This camp, which includes many in government and tech-forward industries, argues that innovation and market mechanisms will decouple economic activity from environmental harm. They point to the falling cost of renewables, the potential of the circular economy, and green export opportunities like sustainable protein and carbon-neutral tourism. Their policy toolkit centres on emissions trading schemes, R&D tax credits, and voluntary corporate pledges. They believe the existing economic system can be retrofitted for sustainability, creating new jobs and wealth in the process.

Side 2: The Proponents of Post-Growth & Te Ao Māori Frameworks

Sceptics, including ecological economists and many kaitiaki, argue that absolute decoupling at the scale and speed required is a dangerous fantasy. They cite data showing that while carbon intensity per dollar of GDP may fall, total global emissions continue to rise. This perspective challenges the primacy of GDP as a measure of progress, advocating instead for holistic wellbeing frameworks like Genuine Progress Indicators (GPI) or He Ara Waiora, which incorporate environmental and social health. From this view, true sustainability requires a fundamental reorientation of values—away from extraction and consumption and towards reciprocity, sufficiency, and the rights of nature itself.

The Middle Ground: A Wellbeing Economy for Aotearoa

The most pragmatic and promising path forward is the explicit adoption of a wellbeing economy model, for which New Zealand is already internationally recognised. This means government budgets and policy assessments are evaluated not solely on their contribution to GDP, but on their impact on natural capital, social cohesion, and intergenerational equity. The Treasury's Living Standards Framework is a nascent tool for this. Advocates should push for this framework to be made mandatory for all significant policy decisions, effectively hardwiring sustainability into the core machinery of government. This moves the debate from "growth vs. environment" to "what kind of growth truly enhances our collective wellbeing?"

Expert Opinion: The Power of "Kaitiakitanga" as Policy Leverage

Here lies a uniquely powerful, yet often underutilised, insight for advocates: Kaitiakitanga is New Zealand's most potent, legally recognised framework for systems-thinking environmental policy. Unlike Western environmentalism, which often fights rearguard actions against degradation, kaitiakitanga is a proactive, holistic, and intergenerational mandate. It understands that the health of the people is inseparable from the health of the land and water.

The expert move is to stop treating Treaty partnerships as a compliance hurdle and start championing them as our greatest strategic advantage. When advocating for freshwater reform, ground your arguments in Te Mana o te Wai. When discussing climate adaptation, centre the disproportionate risks faced by coastal marae and the deep-time resilience knowledge held by iwi. This approach does several things: it provides an unassailable ethical foundation; it connects to legal obligations under the Treaty; and it offers a more compelling narrative than technocratic carbon calculations alone. The upcoming reform of the Resource Management Act is the prime battlefield for this. Advocates must demand that the new Natural and Built Environments Act not only retains but strengthens the principles of partnership and kaitiakitanga, making them the heartbeat of our planning system, not just an appendage.

Debunking Myths: Clearing the Air on Common Misconceptions

- Myth: "Strong environmental policies will crash the New Zealand economy and hurt farmers." Reality: This is a false dichotomy. Inaction poses the far greater economic risk. Our major export markets (the EU, UK) are implementing stringent carbon border adjustments and sustainability requirements. As the RBNZ warns, climate change threatens asset values, insurance affordability, and supply chains. Proactive policy that supports a just transition to low-emission, high-value agriculture future-proofs our largest export sector. Studies, including from the New Zealand Institute of Economic Research, show that targeted investment in sustainable farming practices can boost profitability through premium products and reduced input costs.

- Myth: "Individual consumer choice is enough to drive systemic change." Reality: While conscious consumption is positive, it is insufficient against the scale of the challenge. This myth lets policymakers and corporations off the hook. For instance, even if every Kiwi switched to an EV tomorrow, it would not address the 50% of our emissions that come from agriculture, nor the embodied carbon in our built environment. Advocacy must focus on changing the rules of the game—through regulation, pricing, and investment—to make the sustainable option the default and easiest choice for everyone.

- Myth: "New Zealand's contribution to global emissions is tiny, so our actions don't matter." Reality: This is a failure of moral and economic leadership. Per capita, we are among the highest emitters in the OECD. Our moral authority on the world stage, crucial for trade and diplomacy, hinges on taking credible domestic action. Furthermore, as a developed nation with abundant renewable resources and innovative capacity, we have a responsibility—and an economic opportunity—to develop and export the solutions the world needs.

Costly Mistakes to Avoid in Your Advocacy Campaign

- Preaching to the Choir: Holding rallies where only the already-converted show up feels good but changes little. Solution: Conduct targeted outreach. Invite Federated Farmers representatives to speak on your panel. Write op-eds for The National Business Review. Tailor your message to the values and concerns of the audience you need to persuade.

- Leading with Doom and Gloom: While the science is urgent, a narrative of pure catastrophe can lead to paralysis and disengagement. Solution: Lead with vision and opportunity. Frame policy advocacy as building a more resilient, innovative, and equitable Aotearoa. Tell stories of communities thriving through regeneration, of new jobs in clean tech, of rivers being restored.

- Ignoring the "Just Transition": Demanding rapid change without a plan for those whose livelihoods are affected (e.g., workers in fossil fuels, farmers) creates justifiable opposition and is ethically flawed. Solution: Integrate just transition principles into every policy proposal. Advocate for retraining programmes, regional development funds, and support for communities to lead their own transition plans.

- Neglecting Local Government: The most tangible environmental decisions—on transport, waste, land use, and water—are made by city and regional councils. Solution: Get involved in Long-Term Plan (LTP) consultations, make submissions on district plans, and build relationships with local councillors. Local policy wins create replicable models for national change.

A Contrarian Take: The Strategic Imperative of Embracing "Disruptive" Regulation

Much advocacy politely asks for incremental adjustments: a slightly tighter emissions cap, a modest increase in the waste levy. I propose a more potent strategy: advocate for purposefully disruptive regulation that creates new markets overnight. The most successful environmental policy of the last decade—the phase-out of single-use plastic bags—worked precisely because it was disruptive. It didn't ask supermarkets to please use fewer bags; it banned them, forcing immediate innovation in packaging and consumer behaviour.

We should apply this logic to bigger challenges. Advocate for a mandatory "product stewardship" scheme for all packaging, making producers 100% financially responsible for the end-of-life of their products. This would instantly make reusable and refillable systems economically competitive. Push for a "carbon-negative" building code for all new public housing, creating immediate scale for the mass timber and green concrete industries. This approach moves beyond managing externalities to actively shaping the market in favour of sustainable solutions. It provides the certainty businesses claim they need to invest. The counter-argument will be shrieks of "unworkable!" and "too fast!", but history shows that disruptive regulation, once bedded in, quickly becomes the new normal and unleashes a wave of innovation we can't yet imagine.

Your Actionable Toolkit: Strategies for Effective Advocacy

Moving from insight to impact requires a disciplined approach. Consider this your strategic toolkit.

1. Master the Submission

Public submissions are a fundamental democratic tool. A powerful submission is concise, evidence-based, and solution-oriented. Don't just say "I oppose this." Say, "I oppose Clause 4.2 because it weakens water quality standards. Instead, I propose the following alternative wording, which aligns with the Te Mana o te Wai hierarchy and is supported by the following evidence from ESR science..." Always frame your argument in terms of the policy's own stated objectives.

2. Build Unlikely Alliances

Find common cause with groups outside the traditional green sphere. Partner with health professionals on air quality (burning fossil fuels causes asthma). Partner with insurance companies on climate adaptation (resilient infrastructure saves claims). Partner with iwi on resource management. These coalitions amplify your voice and make it harder for decision-makers to dismiss your concerns as "greenie idealism."

3. Leverage Economic Narratives

Speak the language of risk, opportunity, and cost. Use data from MBIE, the Reserve Bank, and Stats NZ. For example: "MBIE's own data shows the clean-tech sector is growing jobs 40% faster than the rest of the economy. Policy X will stifle this growth." Or, "Failing to invest in wetland restoration now will lead to billions in flood damage costs later, borne by taxpayers."

4. Engage the Electoral Cycle

Advocacy is a marathon, but elections are sprints. Organise candidate forums, asking all parties to state their position on your key issue. Get commitments in writing. Mobilise your network to vote for candidates with strong, credible environmental platforms. Hold them accountable once they are in power.

The Road Ahead: Predictions for the Next Five Years

The coming half-decade will be decisive. Based on current trajectories and expert analysis, we can forecast several key shifts:

- Nature-Based Accounting Goes Mainstream: By 2028, we will see the first major New Zealand corporations and city councils publishing formal natural capital accounts alongside their financial reports, quantifying their dependency and impact on ecosystems. This will fundamentally shift investment and planning decisions.

- The Rise of Climate-Litigation: Following global trends, we will witness landmark climate litigation cases in Aotearoa, where citizens, iwi, or NGOs sue the government or major emitters for failing in their duty of care to protect future generations. These cases will create powerful legal precedents that accelerate policy action.

- Hyper-Localisation of Resilience: As climate impacts intensify, policy will increasingly devolve to communities. We'll see the proliferation of community-led energy co-ops, local food resilience networks, and iwi/hapū-led adaptation plans, with central government shifting to an enabling and funding role.

People Also Ask (FAQ)

What is the most effective first step for a new advocate? Begin hyper-locally. Attend your local council's Environment Committee meeting. Understand their Long-Term Plan. Build a relationship with a councillor. Local wins build confidence, create models, and demonstrate tangible impact faster than focusing solely on Wellington.

How do I engage with businesses that seem resistant? Frame sustainability as risk management, innovation, and brand protection. Use case studies of NZ businesses that saved money through efficiency or gained market share with green products. Speak to their concerns about supply chain security, consumer preferences, and access to green finance.

What role does technology play in modern advocacy? Crucially. Use digital tools for mobilisation (petitions, email campaigns), but also for monitoring. Satellite imagery can track deforestation. Sensor data can monitor river health. Presenting irrefutable, real-time environmental data to policymakers is far more powerful than anecdote.

Final Takeaway & Call to Action

The advocacy for a sustainable Aotearoa is a story we are writing with our actions every day. It requires the courage to challenge powerful incumbents, the empathy to build broad coalitions, the wisdom to centre Te Tiriti partnerships, and the persistence to stay engaged for the long haul. The policies we secure in this decade will determine the health of our land and water for generations to come.

Your mission is clear: Choose one specific policy battle—be it the implementation of the new resource management system, your city's zero-waste strategy, or the next Emissions Reduction Plan. Master the issue. Build your alliance. Craft your compelling, evidence-based, and visionary submission. And then, show up. The waka of change needs every single paddler. The time for passive hope is over; the era of active, strategic advocacy is here. Kia kaha, kia māia, kia manawanui—be strong, be brave, be steadfast.

Related Search Queries

- how to write a submission on NZ environmental policy

- Te Mana o te Wai explained

- New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme reform 2024

- just transition policy Aotearoa

- community climate action groups NZ

- MBIE clean-tech industry report

- Stats NZ environmental-economic accounts

- how to engage with local council on sustainability

- kaitiakitanga in modern resource management

- upcoming NZ government environmental consultations

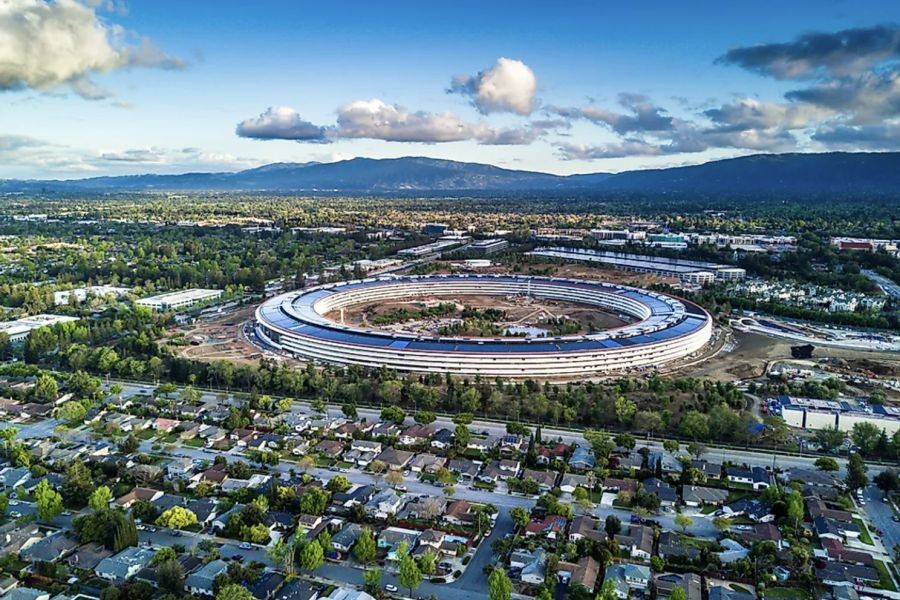

For the full context and strategies on How to Advocate for More Sustainable Environmental Policies in New Zealand – What Works and What Doesn’t in the NZ Market, see our main guide: Video Learning Resources Nz Students.

andersbutls123

1 month ago