“Our clean, green image is fertilised with denial.”

It’s the image on the postcard: rolling hills, pristine rivers, and cows grazing under blue skies. But behind the picturesque landscapes, New Zealand is facing a climate reckoning — and it’s stuck in the paddock.

Despite being one of the world’s biggest agricultural exporters, New Zealand has one of the highest methane emissions per capita, with agriculture making up nearly half of the country’s greenhouse gas output. Yet real, enforceable climate action continues to stall, watered down by powerful farming lobbies, hesitant politicians, and a deep cultural resistance in rural communities.

This article dives deep into the climate politics playing out in the nation’s fields and boardrooms, exploring how the tension between environmental responsibility and economic interests is shaping Aotearoa’s uncertain future.

Part 1: The Emissions Equation — Why NZ’s Climate Numbers Don’t Add Up

New Zealand markets itself as a global leader in sustainability, but the numbers tell a different story. While Aotearoa contributes just 0.17% of the world’s total emissions, it has one of the highest greenhouse gas emissions per capita in the developed world — and agriculture is the driving force behind it.

Breaking Down the Numbers

According to the Ministry for the Environment, around 49% of New Zealand’s greenhouse gas emissions come from agriculture, primarily in the form of:

Methane (CH₄) from livestock (especially dairy cows and sheep)

Nitrous oxide (N₂O) from fertiliser use and animal urine

Carbon dioxide (CO₂) from land-use changes and machinery

This agricultural dominance is unique. In most developed countries, the majority of emissions stem from industry, transport, and energy — but in New Zealand, the rural economy flips the script. This makes tackling emissions politically complex and economically sensitive.

Why Methane Matters

Methane is significantly more potent than carbon dioxide in the short term. Over a 20-year period, it is over 80 times more effective at trapping heat in the atmosphere. While it breaks down faster than CO₂, its immediate impact is critical in the fight to limit global temperature rise.

Yet, under the Zero Carbon Act, biogenic methane (from animals) is treated differently — with softer reduction targets (24–47% by 2050) compared to the goal of net-zero for CO₂ and N₂O. This policy loophole is a direct result of rural lobbying pressure and political compromise.

The Myth of “Efficient Farming”

Industry groups often promote New Zealand farming as "the most emissions-efficient in the world." While this is partially true per unit of product (e.g. litres of milk or kilos of meat), the overall volume of production still makes New Zealand one of the biggest emitters per capita globally.

So while efficiency arguments soothe economic anxieties, they mask the core issue: scale matters. A high-output model, no matter how efficient, still creates enormous environmental stress.

International Pressure Mounts

Global markets are watching. As major trading partners like the EU impose carbon border taxes and demand emissions transparency, New Zealand risks falling behind. Our clean-green brand is a marketing asset — but it's increasingly at odds with the scientific and regulatory reality.

Summary Insight:

New Zealand’s emissions profile is deeply tied to agriculture — a fact that undermines its environmental brand and complicates climate commitments. Without confronting this imbalance, the country risks reputational and ecological decline.

Part 2: The Agribusiness Lobby — Who Really Influences Policy?

In New Zealand, the conversation around climate action in agriculture is not just about science — it’s about power. Behind the delays, diluted policies, and voluntary schemes lies a well-organised and well-funded lobby network representing the interests of agribusiness giants and traditional farming elites.

Who’s at the Table?

Three major industry bodies shape agricultural policy in Aotearoa:

DairyNZ: Representing the dairy sector, one of New Zealand’s largest and most profitable exports.

Beef + Lamb New Zealand: A major player advocating for sheep and beef farmers.

Federated Farmers: A long-standing and politically active group that campaigns on everything from land rights to emissions pricing.

These organisations have seats at most tables where agricultural policy is formed, including He Waka Eke Noa (the climate partnership model) and regular consultations with ministers and ministries.

Political Access and Influence

Agricultural lobbyists have historically enjoyed deep relationships with both major political parties. Election cycles often see rural-friendly policies take priority — not just because of economic importance, but also due to the political cost of upsetting rural voters and industry donors.

In recent years, lobby groups have:

Watered down freshwater reforms, arguing they were “too costly” for farmers.

Delayed or resisted emissions pricing, insisting more research is needed before action.

Pushed for government subsidies for innovation and technology that reduces emissions — but without binding reduction targets.

The result? A government trying to please everyone — and achieving little.

Science vs Strategy

While the scientific consensus is clear about the urgent need to reduce methane and nitrous oxide, agribusiness lobbying often reframes the issue as one of “economic security” or “international competitiveness.” This strategic narrative pits environmentalists and policymakers against hardworking farmers, creating public division and stalling reform.

Their messaging often relies on a simple but effective emotional appeal: “We feed the world, and now we’re being punished for it.”

Regulatory Capture in Action

The concept of regulatory capture — where industry players effectively control the agencies meant to regulate them — is increasingly visible in New Zealand’s agricultural landscape. Policies are crafted with input from those they’re meant to govern, leading to weak accountability, slow timelines, and voluntary rather than enforceable action.

Summary Insight:

Agribusiness lobbies in New Zealand wield extraordinary influence over climate policy. Their power helps shape laws, delay emissions pricing, and protect short-term profits — often at the expense of long-term environmental sustainability.

Part 3: He Waka Eke Noa — Partnership or Political Delay Tactic?

At first glance, He Waka Eke Noa — the government–industry partnership designed to reduce agricultural emissions — looks like a collaborative, nation-leading climate solution. But critics say it’s more waka than wind: a vessel designed to drift rather than deliver.

What Is He Waka Eke Noa?

Launched in 2019, He Waka Eke Noa was promoted as a world-first approach to bringing farmers into New Zealand’s climate framework without forcing them into the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS).

Its goal:

To design a sector-led pricing mechanism for agricultural emissions (mainly methane and nitrous oxide) by 2025, with measurable reductions and clear accountability.

Instead of regulating from above, the government invited industry leaders — including DairyNZ, Beef + Lamb NZ, and Federated Farmers — to help shape the rules they’d eventually have to follow.

Promises Made, Deadlines Missed

Five years later, the partnership has failed to deliver a credible, binding emissions pricing model. Key milestones have been delayed multiple times. When proposals did surface, they included:

Lenient pricing options far below the social cost of methane

Exemptions for small farms

Delays in enforcement until post-2025

Reliance on “future technologies” not yet scalable

This has led many to question whether He Waka Eke Noa was ever intended to produce meaningful emissions reductions — or simply to keep farmers out of the ETS indefinitely.

Criticism from Experts and Environmental Groups

Climate scientists, economists, and environmental groups argue that He Waka Eke Noa has become a political buffer zone, absorbing pressure for action while avoiding hard decisions.

Notably:

The Climate Change Commission (CCC) has warned that voluntary pricing lacks credibility and urgency.

Greenpeace has labelled the scheme a greenwashing exercise, allowing the government to appear proactive without challenging rural interests.

Indigenous and environmental leaders have pointed out that Māori landowners and regenerative farmers are underrepresented in the framework.

A Missed Opportunity?

New Zealand could have led the world with a bold, science-based agricultural emissions strategy. Instead, He Waka Eke Noa risks becoming a case study in political stalling: a voluntary process that satisfied no one, delivered little, and allowed emissions to rise unchecked.

Summary Insight:

He Waka Eke Noa was framed as a partnership — but critics argue it became a political shield for inaction. Without binding targets or accountability, the scheme has delayed real climate progress while shielding agribusiness from regulation.

Part 4: Rural Identity and the Resistance to Change

To understand why New Zealand’s agricultural climate policy is stuck, we have to go beyond economics and politics — and look at culture. For many farmers, especially in regions like Waikato, Southland, and Canterbury, climate regulations don’t just feel like policy shifts. They feel like a personal attack on identity, tradition, and legacy.

Farming as Identity, Not Just Work

In rural Aotearoa, farming isn’t just a job. It’s whakapapa. Land has been passed down through generations — not only as a source of income, but as a marker of pride, endurance, and belonging. For many Pākehā farmers, especially, their connection to the land is as deep-rooted as any cultural identity in the country.

This makes the climate conversation emotionally charged. Being told to reduce herds, change soil practices, or cut methane emissions isn’t heard as “Save the planet” — it’s heard as “You’re doing harm,” or worse, “You’re the villain.”

“They Don’t Understand Us”

A common sentiment in rural communities is that urban elites, academics, and politicians “don’t understand” farming life. From Wellington and Auckland, sweeping policies can seem logical and necessary. But on the farm, they can feel disconnected from the daily grind of unpredictable markets, weather events, rising costs, and long hours.

This city–country disconnect creates a breeding ground for resentment and resistance, especially when climate activists are seen as naïve or condescending.

The Rise of Rural Populism

In recent years, groups like Groundswell NZ have emerged as loud voices of farmer frustration. What started as a protest against freshwater and emissions reforms quickly morphed into a rural populist movement, tapping into wider discontent about regulation, bureaucracy, and the perception of being “scapegoated” for climate change.

This sentiment is further inflamed by misinformation campaigns that exaggerate the costs of reform or downplay the climate science altogether.

The Role of Intergenerational Pressure

Young people growing up on farms often inherit not just the land, but the burden of maintaining a legacy. This can make it harder to pivot toward change, even if they’re more open to environmental solutions. Cultural expectations, debt, and the fear of being “the generation that failed the farm” keep many trapped in unsustainable models.

Summary Insight:

Rural resistance to climate policy in New Zealand isn’t just economic — it’s cultural. Without recognising the identity and emotion tied to farming, even the best-intended policies will face backlash and inertia. Change must be empathetic, inclusive, and locally grounded.

Part 5: The Cost of Inaction — Environmental and Global Reputational Risk

New Zealand’s reluctance to regulate agricultural emissions isn't just a domestic policy problem — it’s a growing liability with consequences that stretch from freshwater streams to foreign trade tables. As climate deadlines loom and environmental degradation worsens, the cost of doing nothing is quickly outweighing the political comfort of delay.

Environmental Degradation on the Ground

While the national debate often centres on carbon budgets and pricing frameworks, the most visible consequences of inaction are local and lived:

Waterways polluted by nitrate runoff and effluent from intensive dairying are now a national concern. Many rivers and lakes once safe for swimming are now health hazards.

Soil quality is declining due to over-farming, fertiliser overuse, and monoculture grazing.

Biodiversity loss is accelerating. Native wetlands — natural carbon sinks — have been drained for pasture at an alarming rate, and native species are being pushed to the brink.

Despite Aotearoa's image as a green paradise, the ecological reality paints a far more troubled picture — one driven in large part by an agricultural system that has outgrown its ecological limits.

The Global Market Is Watching

New Zealand’s export economy depends heavily on international perceptions of sustainability. Products like dairy, meat, wine, and fruit trade on the country's “clean, green” brand — but increasingly, that brand is being questioned.

Key trading partners — including the EU and UK — are implementing carbon border adjustments and stricter environmental certifications. Without verifiable emissions reductions and sustainable practices, New Zealand producers risk:

Losing market access or facing tariffs

Facing brand erosion in premium markets

Being excluded from international sustainability benchmarks

If New Zealand can't back up its image with measurable action, the export economy — particularly for boutique and premium products — is at risk of serious damage.

Tourism’s Green Illusion

Tourism is another sector riding on the country's natural reputation. But as international travellers become more climate-conscious, glossy marketing campaigns are being scrutinised. It’s one thing to sell serenity; it’s another to defend the environmental record that underpins it.

This reputational disconnect is now a liability. Critics accuse New Zealand of greenwashing — using its native beauty to distract from poor climate performance, especially in agriculture.

Climate Litigation and Financial Risk

Around the world, governments, corporations, and even farmers are being sued over emissions, pollution, and climate damage. New Zealand is not immune. Inaction may soon carry legal and financial costs:

Climate-related lawsuits targeting policy failures

Insurance losses from extreme weather events exacerbated by emissions

Investment risk as global funds pull out of carbon-intensive industries

Summary Insight:

New Zealand’s refusal to confront agricultural emissions isn’t just bad for the environment — it’s dangerous for its global reputation, its trade economy, and its legal resilience. The cost of inaction is already here — and rising.

Part 6: Greenwashing the Brand — “Clean, Green New Zealand” Under Scrutiny

For decades, Aotearoa has sold itself to the world as a pristine paradise — “100% Pure,” a land of mountains, rivers, and rolling green pastures. But behind this glossy façade lies a widening credibility gap. Environmental experts, trade partners, and even New Zealanders themselves are beginning to question: is the brand a reality, or a marketing illusion?

The Origins of the Myth

The “Clean, Green New Zealand” image was born in the 1990s, when tourism campaigns promoted the country as untouched, natural, and eco-forward. It worked. The brand boosted exports, drove tourism, and helped position New Zealand as a progressive voice in global environmental issues.

But as emissions data, freshwater degradation, and biodiversity loss mount, the disconnect between image and action has become harder to hide.

The Rise of Greenwashing Accusations

International observers are no longer buying the hype. Multiple reports — including from the OECD and UN — have flagged inconsistencies between New Zealand’s environmental promises and actual performance.

Critics highlight:

One of the highest per-capita emission rates in the developed world

Polluted waterways, particularly in dairy-heavy regions

Insufficient action on climate, especially in agriculture

Continued habitat destruction of native flora and fauna

When a country promotes itself as an environmental leader but fails to meet its own goals, it’s not leadership — it’s greenwashing.

Trade and Tourism at Risk

Greenwashing doesn’t just undermine credibility — it jeopardises economic sectors:

Tourists expecting purity are confronted with warnings about unsafe swimming spots and degraded ecosystems.

Exporters face scrutiny from eco-conscious consumers demanding genuine sustainability.

Sustainability certifications are becoming stricter, and New Zealand risks being left behind if its green claims aren’t backed by action.

In premium markets like Europe, where climate policy is tightening, perception matters — and perception is shifting.

The Cultural Tension Within

Many New Zealanders take pride in the country’s natural beauty and biodiversity. But there’s growing discomfort — even shame — around the gap between how we present ourselves and what we actually do. The tension is felt most by rangatahi (youth), Māori kaitiaki (guardians), environmental advocates, and rural regenerative farmers who see both the beauty and the damage firsthand.

Summary Insight:

New Zealand’s environmental brand, once a source of pride, now risks collapse under the weight of its contradictions. Without bold, measurable climate action — especially in agriculture — the country faces not just ecological failure, but reputational collapse.

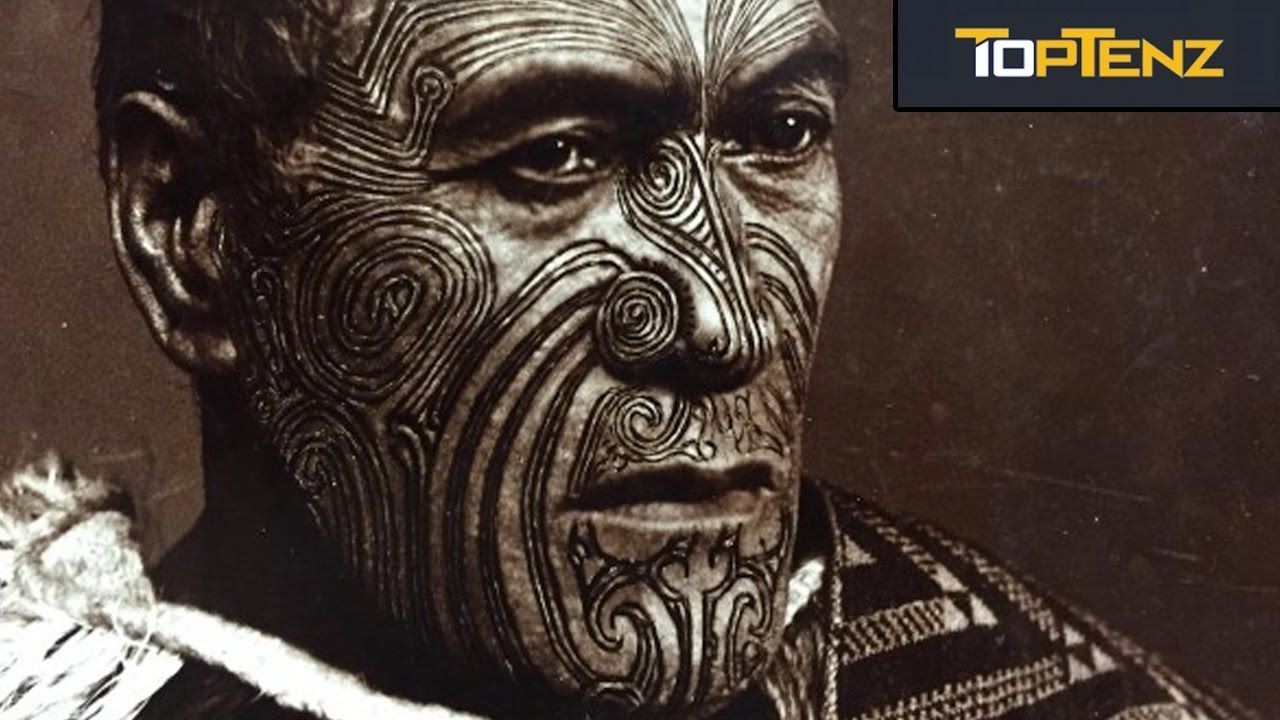

Part 7: Māori Perspectives — Kaitiakitanga and a Different Way Forward

Amid political lobbying and climate gridlock, Māori voices offer a perspective rooted not in short-term profit but in intergenerational responsibility. At the heart of this worldview lies kaitiakitanga — the obligation to protect and nurture the natural world. Unlike extractive models of agriculture, kaitiakitanga positions people not as owners of land, but as its stewards.

What Is Kaitiakitanga?

Kaitiakitanga is a Māori environmental ethic based on whakapapa (genealogy), mana (authority and responsibility), and mauri (life force). It acknowledges that:

Land, water, and sky are ancestors, not resources.

Every action has long-term ripple effects on future generations.

Wellbeing is collective, spanning people, ecosystems, and time.

This contrasts sharply with industrial farming models driven by yields, efficiency, and short-term gain.

Marginalised in the Climate Conversation

Despite offering a deeply sustainable framework, Māori have often been sidelined in national climate and agricultural policymaking. Māori landowners:

Control significant whenua Māori (ancestral land), often in marginal or less productive areas.

Face legal and economic barriers to developing land in climate-smart ways (due to complex land tenure and underinvestment).

Are underrepresented in major policy forums like He Waka Eke Noa.

The irony is sharp: the Indigenous people of Aotearoa, with a relational and ecological worldview, are largely excluded from shaping policies about the land and environment.

Indigenous Models in Practice

There are, however, powerful examples of Māori-led innovation:

Regenerative Māori farming collectives that reduce inputs, restore biodiversity, and re-integrate mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge).

Iwi-led conservation projects, such as pest control and wetland restoration, that centre both ecological and cultural health.

Māori climate adaptation plans, particularly in coastal regions, that blend Western science with Indigenous knowledge systems.

These models demonstrate that Māori leadership isn’t just symbolic — it’s practical, proven, and deeply needed.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi and Environmental Justice

Climate inaction also raises questions of Treaty justice. Te Tiriti o Waitangi guarantees Māori partnership in national governance — including environmental management. Yet decisions are still being made without full Māori participation, in ways that undermine rangatiratanga (self-determination) and ecological integrity.

If Aotearoa is to honour the Treaty and build a genuinely sustainable future, Māori leadership must be central — not tokenised.

Summary Insight:

Māori approaches to land and climate, grounded in kaitiakitanga, offer a vital path forward. But until Māori are given true authority and partnership in environmental policy, New Zealand will continue to ignore one of its most powerful tools for climate resilience.

Part 8: Regenerative Farming — What Real Change Could Look Like

If industrial agriculture is part of the climate problem, regenerative farming could be a powerful part of the solution. While political debates stall and emissions rise, a growing number of farmers in Aotearoa are already proving that a different model is possible — one that heals the land while still producing food, jobs, and community resilience.

What Is Regenerative Farming?

Regenerative agriculture goes beyond sustainability. While sustainable farming aims to reduce harm, regenerative farming seeks to actively restore ecosystems.

Key principles include:

Building soil health by avoiding synthetic fertilisers and tilling

Using cover crops and rotational grazing to enhance biodiversity

Retaining water and carbon in the soil through native plantings and composting

Reducing herd size while improving animal welfare

Working with natural cycles, not against them

Unlike industrial models focused on maximising yield per hectare, regenerative farming prioritises long-term resilience, both ecological and economic.

Regenerative Farms in Aotearoa

Across the motu, small and mid-sized farms are quietly leading a regenerative revolution:

Mangarara Station in Hawke’s Bay has transitioned from a conventional sheep and beef operation into a model of mixed, holistic land use, combining native reforestation, rotational grazing, and eco-tourism.

Pāmu (Landcorp) — a state-owned enterprise — has trialled regenerative practices across several of its farms with encouraging results in biodiversity and water retention.

Indigenous farming collectives, like those supported by Te Tumu Paeroa, are merging mātauranga Māori with regenerative methods to create culturally and ecologically rooted models.

These farmers are not waiting for perfect policy — they’re already proving change is both possible and profitable.

The Barriers to Scaling Up

Despite its promise, regenerative agriculture faces steep structural barriers in New Zealand:

Lack of financial incentives: The current system rewards scale and yield, not soil health or biodiversity.

Industry resistance: Large agribusiness players profit from the status quo of fertilisers, feed supplements, and monocultures.

Policy lag: Government support still favours low-ambition reforms over bold transformation.

Educational gaps: Most agricultural training still promotes industrial models.

Without significant shifts in subsidies, land-use planning, and training, regenerative farming risks remaining niche — admired but unsupported.

Why Regeneration Matters Now

As climate impacts grow — floods, droughts, erosion — resilience will become more valuable than yield. Regenerative farms can:

Sequester carbon

Withstand extreme weather

Reduce reliance on volatile global inputs

Rebuild rural communities from the ground up

Most importantly, they offer a future in which farming doesn’t come at the cost of freshwater, climate stability, or biodiversity.

Summary Insight:

Regenerative agriculture isn’t a fantasy — it’s already here. But without bold support, it will remain on the margins while industrial systems continue to dominate and degrade. Scaling up regeneration could transform farming from climate villain to climate hero.

Part 9: Political Paralysis — Why Policy Keeps Protecting the Status Quo

Despite the science, the protests, and the urgent environmental data, New Zealand’s agricultural emissions policy remains toothless. Why? Because real change threatens powerful interests — and few politicians are willing to risk that fight. At the heart of New Zealand’s climate stagnation is not a lack of solutions, but a failure of political courage.

The Influence of Agribusiness Lobbies

Agriculture is not just New Zealand’s largest emitter — it’s also one of its most politically powerful industries.

Groups like Federated Farmers, DairyNZ, and Beef + Lamb NZ wield significant influence through:

Lobbying and policy consultation

Public messaging campaigns that frame farmers as victims of regulation

Back-channel access to ministers and decision-makers

Strong rural media presence, which shapes public perception and resistance

These organisations often position themselves as representatives of “the farmer on the ground,” but their messaging is aligned more with large-scale corporate agribusiness than with small regenerative operations.

He Waka Eke Noa: A Compromise Too Far?

The government’s flagship policy attempt — He Waka Eke Noa, a public–private partnership on agricultural emissions pricing — was supposed to be a step forward. But in practice, it’s become a vehicle for delay.

Key issues include:

Voluntary targets with no real enforcement

Complex measurement systems that are inaccessible for small farmers

Delayed implementation that keeps pushing action years into the future

Pushback from both environmentalists and farmers, each for different reasons

Rather than setting firm limits on emissions, the scheme risks locking in weak commitments and avoiding meaningful change.

Political Fear of Rural Backlash

Rural seats remain vital in elections — and the image of a “government against farmers” is politically toxic. Parties on both the left and right fear:

Losing votes in key rural electorates

Being painted as anti-farming or urban-elitist

Fueling protest movements like Groundswell or ACT-aligned campaigns

This has led to a pattern of backpedalling and watered-down reforms under successive governments, despite growing evidence that stronger action is both necessary and feasible.

Media’s Role in Polarisation

Media coverage often frames the climate debate as a binary: activists vs. farmers, cities vs. country, progress vs. tradition. This oversimplification fuels division and leaves little space for nuanced voices — including farmers who support reform, Māori landowners with different visions, or scientists offering balanced strategies.

Summary Insight:

New Zealand’s political system is trapped between climate obligation and agribusiness influence. Until policymakers are willing to confront this power imbalance and lead with principle over popularity, the country will remain stuck in the paddock — with its climate credibility on the line.

Part 10: A Way Forward — Reimagining Climate Leadership in Aotearoa

New Zealand’s climate challenges are undeniably complex, but they are not insurmountable. The key lies in bold leadership that embraces innovation, inclusivity, and urgent action. To reclaim its “clean, green” reputation and secure a sustainable future, Aotearoa must rethink how it governs its land, people, and climate responsibilities.

Centre Māori Leadership and Partnership

True climate leadership must begin by honouring Te Tiriti o Waitangi — recognising Māori as partners with tino rangatiratanga (self-determination) over their lands and waters. This means:

Embedding Māori knowledge (mātauranga Māori) and values like kaitiakitanga in all climate policy.

Enabling iwi and hapū to lead adaptation and mitigation strategies on their whenua.

Supporting Māori-led regenerative agriculture and conservation initiatives.

This approach is both a Treaty obligation and a pathway to more effective, culturally grounded solutions.

Prioritise Regenerative Agriculture and Just Transitions

The government must shift financial and regulatory support away from industrial farming and towards regenerative practices. This includes:

Offering incentives, subsidies, and training for farmers transitioning to low-emission, soil-restoring methods.

Ensuring rural communities have access to economic diversification and support to thrive in a low-carbon future.

Creating transparent, fair emissions pricing that accounts for on-farm realities without burdening smallholders disproportionately.

A just transition is essential to maintain social cohesion and economic stability.

Strengthen National Climate Governance

Climate leadership requires strong institutions and clear targets. Aotearoa should:

Set legally binding agricultural emissions reduction targets aligned with the Paris Agreement.

Improve data collection and monitoring to measure progress accurately.

Foster cross-sector collaboration — bringing together government, industry, Māori, scientists, and communities.

Clear accountability mechanisms will build trust and ensure sustained momentum.

Rebuild Public Trust and Dialogue

Polarisation and distrust have fractured the climate conversation. Leaders must:

Facilitate honest, inclusive dialogue that respects diverse perspectives and experiences.

Communicate clearly about the necessity and benefits of change — from environmental health to long-term economic security.

Counter misinformation with evidence-based education and community engagement.

Building social licence is as crucial as technical solutions.

Invest in Innovation and Resilience

Finally, leadership means investing in research and innovation:

Develop climate-resilient crops, improved soil carbon technologies, and alternative protein sources.

Support Māori science initiatives blending traditional knowledge with cutting-edge research.

Enhance climate adaptation infrastructure — from flood defenses to drought-resistant landscapes.

Innovation will help Aotearoa not only cope with change but thrive within it.

Summary Insight:

Reimagining climate leadership in New Zealand requires courage, inclusivity, and vision. By centring Māori partnership, supporting regenerative farming, and strengthening governance, Aotearoa can move beyond greenwashing to genuine sustainability — securing a resilient future for all.

Conclusion: Time to Step Up and Transform Aotearoa’s Climate Future

New Zealand stands at a crossroads. The image of a “clean, green” paradise is being undermined by rising emissions, political inertia, and entrenched industrial farming. Yet, within this challenge lies an opportunity — to listen to Māori voices, empower regenerative farmers, and embrace bold climate leadership that honours Te Tiriti o Waitangi and protects the whenua for generations to come.

The stakes could not be higher. Our rivers, soils, and communities depend on urgent, transformative action. The future of farming, the health of the planet, and the integrity of our national identity all hang in the balance.

Call to Action: Join the Movement for a Just and Sustainable Aotearoa

For policymakers: Commit to strong, enforceable climate targets that centre Māori leadership and support regenerative agriculture.

For farmers and landowners: Explore and adopt regenerative practices that restore the land and build resilience.

For all New Zealanders: Stay informed, demand transparency, and support businesses and initiatives that prioritise sustainability and justice.

For communities and educators: Foster open, honest conversations about climate realities and solutions — breaking down myths and polarisation.

Together, we can turn the tide on climate stagnation and lead the world in creating a truly sustainable, thriving New Zealand. The paddock is waiting — it’s time to grow change from the ground up.