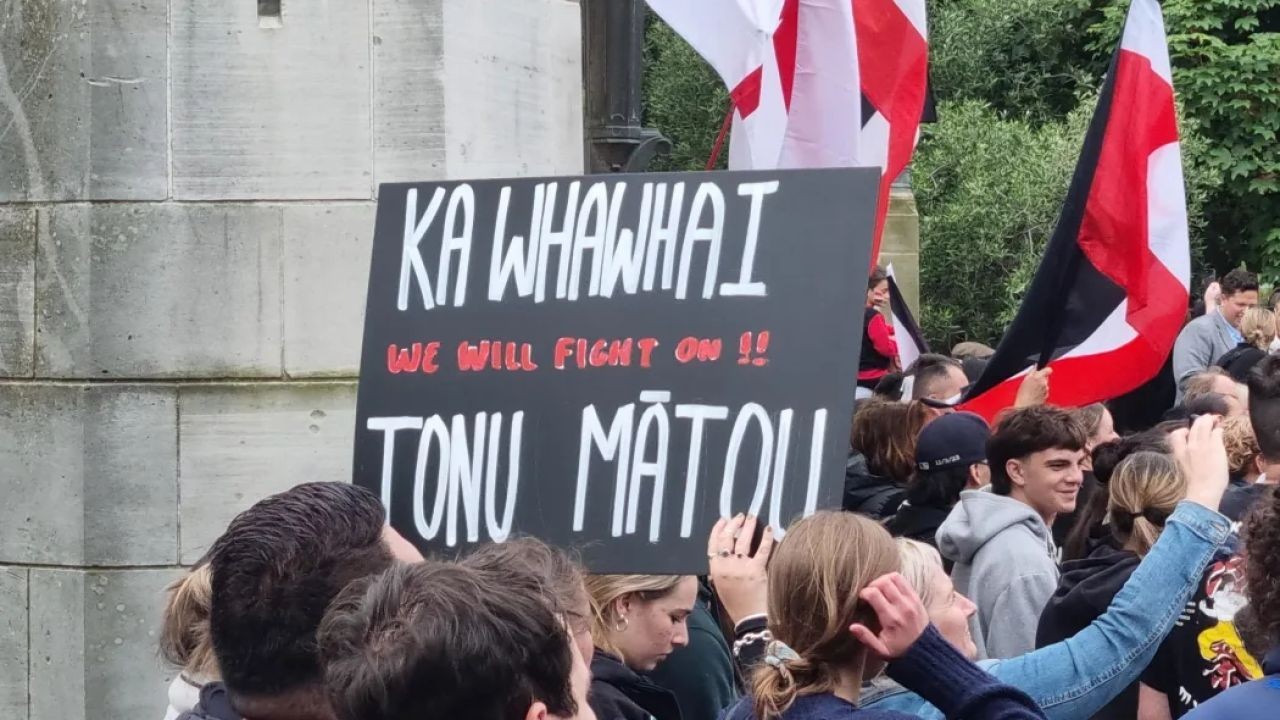

Welcome to New Zealand — the land of breathtaking landscapes, warm ‘kia ora’ greetings, and a complex cultural mosaic. But behind the friendly façade lies a tension many migrants and locals feel: the expectation to leave their culture at the border and fit into a narrow idea of what it means to be ‘Kiwi.’ In this article, we dive deep into why migration itself isn’t the problem for Aotearoa, but the pressures to assimilate, become ‘white-adjacent,’ and erase cultural identities threaten the rich diversity that makes New Zealand unique.

From the history of migration waves to contemporary anti-immigrant sentiments, we explore the clash between multicultural marketing messages and monocultural social expectations. We hear voices from immigrants who navigate this tricky terrain and look at how these dynamics impact Māori and Pasifika communities. Finally, we explore pathways towards authentic inclusion and a reimagined Kiwi identity — one that celebrates difference instead of demanding conformity.

Part 1: The Illusion of the ‘Kiwi’ Identity

New Zealand prides itself on being a land of friendly people, where “Kia ora” is a daily greeting and the spirit of manaakitanga (hospitality) is celebrated. Yet, beneath this welcoming veneer lies a complex and often contested national identity — one that frequently asks newcomers to shed their cultural roots to fit a narrow definition of what it means to be ‘Kiwi.’

The ‘Kiwi’ identity has historically been tied to a monocultural ideal rooted in Pākehā settler narratives. It imagines the “typical” New Zealander as someone who speaks English with a certain accent, enjoys rugby and the outdoors, and embraces Western norms and values. This ideal often sidelines the realities of a multicultural, multiethnic society that is home to Māori, Pasifika, Asians, Europeans, Africans, and many other communities.

For many migrants, the pressure to conform to this dominant ‘Kiwi’ ideal can feel like an erasure of their true selves. The subtle — and sometimes overt — expectation is to become ‘white-adjacent’: to downplay cultural practices, languages, and identities that differ from the mainstream. This process of assimilation doesn’t just affect newcomers; it also shapes how locals perceive what counts as “authentically Kiwi.”

Yet, this illusion overlooks the truth that New Zealand has always been a place of migration and cultural exchange. From the early Polynesian navigators to waves of European settlers and recent immigrants from Asia and beyond, the country’s identity is, and always has been, evolving and diverse.

Understanding this tension is crucial. When the ‘Kiwi’ identity becomes a gatekeeper for belonging, it fosters exclusion, erodes cultural richness, and fuels the anti-immigrant sentiments that sometimes bubble to the surface in public discourse.

Daniel Chyi on the ‘Kiwi’ identity:

“True New Zealand identity isn’t about fitting into a narrow mould — it’s about embracing all the cultures and stories that make up our nation. When we demand assimilation instead of inclusion, we lose the very diversity that strengthens us.”

— Daniel Chyi, Co-founder, Vidude.com

Part 2: The History of Migration to Aotearoa

To understand the tensions surrounding identity, migration, and assimilation in modern New Zealand, we must first step back and confront the layered and often uncomfortable history of how people have come to this land — beginning long before it was called “New Zealand.”

Polynesian Settlement and the Rise of Māori

The first people to arrive in Aotearoa were Polynesian navigators — seafarers of immense skill and knowledge. Around 1250–1300 CE, these voyagers settled in Aotearoa and formed the foundation of what we now know as the Māori people. They brought with them rich traditions, oral histories, sophisticated environmental management systems, and a worldview deeply rooted in whakapapa (genealogy), whenua (land), and whanaungatanga (relationships).

For centuries, Māori thrived across the islands — developing iwi, hapū, and complex social systems — with no concept of immigration as we understand it today. Movement and belonging were tied to ancestral links to the land and kinship networks, not state borders or assimilation policies.

European Colonisation: Migration Meets Imperialism

The second major wave of migration began in the 18th and 19th centuries, when European explorers and missionaries arrived, followed by settlers, soldiers, and colonists. Unlike the Polynesian arrival, this wave was not simply about movement or exchange — it was about control.

The signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi in 1840 between Māori rangatira and the British Crown was meant to establish a relationship of mutual respect and guardianship. But almost immediately, the Crown violated the agreement, using it as a tool to justify mass land confiscations, warfare (such as the New Zealand Wars), and the marginalisation of Māori authority.

These European settlers were not simply migrants — they were colonists, arriving with the backing of an empire that imposed its language, laws, economy, and religion onto an existing Indigenous society.

From White New Zealand to Multicultural NZ?

By the early 20th century, New Zealand immigration policy was largely shaped by a desire to remain a “Britain of the South.” This included explicitly racist policies such as the Chinese Poll Tax (1881) and restrictions on non-European immigrants. For decades, Pākehā identity was reinforced through education, governance, and media, creating a dominant monocultural narrative that elevated whiteness as the norm.

It wasn’t until the 1970s and 80s — amidst global shifts, Pacific Island migration, and Māori activism — that Aotearoa began slowly reimagining itself as a multicultural society. Policies changed, populations diversified, and multiculturalism became an official part of national branding.

But deeper social attitudes haven’t always kept up with these policy shifts.

Multicultural by Numbers — But Not Always in Practice

Today, over 27% of New Zealand’s population was born overseas, and the country is home to communities from China, India, the Philippines, South Africa, Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, and many others. Auckland is often described as one of the most diverse cities in the world.

And yet — the promise of inclusion doesn’t always match lived reality. Many immigrants face racism in schools, housing discrimination, employment barriers, and subtle pressures to leave their language and traditions at the door.

Daniel Chyi on Migration and Power:

“There’s a big difference between migration and colonisation. Migrants come to contribute — not to conquer. But too often, the structures left by colonisation still expect everyone else to assimilate to them. That’s not inclusion. That’s just a softer kind of erasure.”

— Daniel Chyi, Co-founder, Vidude.com

In short, New Zealand has always been shaped by migration — but the power dynamics behind each wave of movement have not been equal. Today’s immigrants are often held to standards that ignore this complex history and push them to conform to systems they had no hand in creating.

Part 3: Anti-Immigrant Sentiment in a “Friendly” Nation

New Zealand loves to think of itself as a warm, open, and welcoming place. And in many ways, it is. Kiwis pride themselves on their friendliness, laid-back culture, and international reputation for being “good sorts.” But beneath the surface of this national self-image lies a contradiction: a persistent undercurrent of suspicion, resentment, and exclusion directed at migrants — particularly those who don’t assimilate quietly.

This is the paradox of New Zealand’s “friendly racism.”

Nice to Your Face — But Not at the Policy Table

New migrants to Aotearoa often speak of the polite smiles they receive on the street, the “kia ora!” in passing, and neighbours who might offer a cuppa or a bit of banter. But when it comes to employment, housing, political representation, or even casual conversation, the friendliness often stops at the surface.

Many migrants report being asked questions like:

“But where are you really from?”

“Do you speak English?”

“Why are there so many of your people coming here?”

It’s the kind of low-level prejudice that doesn’t always make headlines — but it accumulates. And it undermines the myth of full inclusion.

Immigration as a Scapegoat

When housing prices skyrocket, when healthcare services are stretched, when schools are under-resourced — it’s not uncommon to hear talkback radio or online comment sections blaming “too much immigration.” Despite the fact that most migrants are working, paying taxes, and contributing to the economy, they’re often framed as a burden or as culturally incompatible.

Politicians across the spectrum have quietly or openly stoked these fears. Calls for “values tests,” “English language thresholds,” or “population balance” have all been coded ways of saying: “We want immigrants who act like Pākehā.”

In times of economic stress or national uncertainty, immigrants have too often become the convenient punching bag.

The Christchurch Attacks: A National Reckoning

On 15 March 2019, New Zealand faced a tragic and brutal wake-up call: a white supremacist terrorist attacked two mosques in Christchurch, murdering 51 people and injuring dozens more. Many of the victims were immigrants — Muslims from countries like Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Somalia.

The aftermath prompted a moment of national unity, with massive outpourings of grief and support. But it also forced Aotearoa to look in the mirror.

This wasn’t just an imported ideology. The terrorist cited New Zealand political discourse in his manifesto. Local Muslims had already been warning about rising racism, targeted harassment, and surveillance well before the attack.

The truth: Aotearoa’s kindness narrative had allowed some people to ignore the racism that was always there.

Daniel Chyi on the Myth of Kiwi Niceness:

“Kiwis are famously friendly — but we’ve got to stop confusing friendliness with fairness. You can smile at your new neighbour while still voting for policies that keep their kids locked out of opportunity. Real inclusion means more than a ‘kia ora’ — it means ceding space, power, and narrative.”

— Daniel Chyi, Co-founder, Vidude.com

The “Good Migrant” vs “Bad Migrant” Trap

New Zealand doesn’t dislike all migrants. It just prefers the ones who blend in, stay quiet, and don’t challenge the dominant culture. This creates a “good migrant” vs “bad migrant” binary:

A good migrant is grateful, hardworking, apolitical, and eager to assimilate.

A bad migrant speaks up, preserves their culture, or questions the status quo.

This dynamic forces immigrants to police themselves — their dress, their language, even their parenting — to avoid making Pākehā uncomfortable. It’s a psychological toll that can be exhausting and dehumanising.

The Result? Quiet Isolation

Many immigrants end up feeling invisible, even as they are asked to constantly prove their loyalty. From South Auckland to Invercargill, migrant communities often feel tolerated rather than celebrated — a presence allowed, but not fully welcomed.

For all the multicultural festivals and marketing, real structural inclusion — in leadership, in the curriculum, in media, and in policy — remains limited.

Part 4: “Fitting In” or Giving In? The Pressure to Assimilate in Daily Life

For many immigrants and their children in Aotearoa, the unspoken rule is clear: “You’re welcome here — as long as you don’t make us uncomfortable.”

This is assimilation by quiet coercion. The pressure to flatten one’s accent, anglicise your name, eat your lunch in private, and celebrate your traditions discreetly — or not at all. You’re encouraged to participate, but only if you behave in a way that doesn’t disturb the fragile illusion of cultural sameness.

New Zealand’s “diversity” is often celebrated — but only when it’s photogenic, non-political, and commercially convenient.

The Hidden Curriculum of Kiwi Culture

Schools, workplaces, sports clubs — these are places where Kiwi values are absorbed without being explicitly taught. And one of those values is: don’t be too different.

If you’re a migrant child in school:

You might be mocked for your lunch.

Your name might be butchered or casually shortened.

Your holidays and holy days might be ignored entirely.

Your parents might be told not to speak their language at home because it “confuses” you.

If you’re an adult migrant:

Your overseas qualifications might not be recognised.

You might be encouraged to adopt an “easier” name to get interviews.

You’re told to “network more” — but those networks are closed circles built on long-standing Kiwi social capital.

Assimilation becomes survival.

Daniel Chyi on Cultural Flattening:

“What we call ‘fitting in’ is too often just giving up. Migrants aren’t being asked to integrate — they’re being asked to erase. That’s not multiculturalism; that’s quiet colonisation. And it makes communities smaller, sadder, and less honest.”

— Daniel Chyi, Co-founder, Vidude.com

The Cost of “Belonging”

When you’re constantly made to feel like an outsider unless you mimic the majority, it creates a psychological divide:

Do I stay true to who I am — and risk exclusion?

Or do I shrink myself — and gain conditional acceptance?

For many, the cost of “belonging” is cultural silence. Migrants pass down the message to their kids: “Don’t rock the boat. Be polite. Speak English. Blend in.”

Over time, this creates a second-generation loss: heritage languages vanish, traditional knowledge gets buried, and the richness of identity gets replaced by insecurity.

When Inclusion Requires Invisibility

The subtle racism of New Zealand is that it doesn’t always say “no” to difference — it just ignores it. The message isn’t direct rejection. It’s indifference.

Multiculturalism here often stops at food stalls and fusion festivals. Deep inclusion — in school curricula, public leadership, national storytelling — remains minimal. Meanwhile, many migrants feel like they’re stuck in a cultural waiting room: allowed inside, but never fully invited to sit at the table.

The Rebellion Against Assimilation Is Rising

But things are shifting. Younger Kiwi migrants are reclaiming their accents, embracing their names, and pushing back on monocultural expectations. They’re speaking up on social media, demanding inclusive workplaces, and refusing to apologise for who they are.

This is where platforms like Vidude.com step in — giving diverse creators the space to speak, teach, and share on their own terms. No algorithm bias. No “safe for sponsors” filter. Just real voices, raw and local.

Part 5: White-Adjacent or Whitewashed? The Myth of ‘Successful’ Migrants in Aotearoa

In New Zealand, the idea of a “good migrant” is often shaped less by actual contribution and more by cultural compliance.

You’ve “made it” if you:

Speak unaccented English.

Land a white-collar job.

Send your kids to a decile 10 school.

Avoid politics, “controversial” opinions, or complaints about racism.

But behind that thin layer of acceptance is a deeper question: Are you being celebrated — or simply tolerated because you’ve learnt how to mimic whiteness?

Success Redefined Through a Pākehā Lens

In media, education, and business, successful migrants are usually those who fit in seamlessly — not those who challenge, expand, or redefine what Kiwi identity looks like.

This idea of "white-adjacency" is insidious. It rewards silence over selfhood. It measures achievement not by cultural richness, but by proximity to dominant (often Pākehā) norms.

Even those with money, degrees, or visibility often find their success limited by invisible ceilings — unless they stay quiet on structural injustice.

Daniel Chyi on the White-Adjacent Trap:

“Assimilation is not success. And whitening yourself isn’t growth. Real inclusion means we don’t just welcome different faces — we accept different values, voices, and truths. Until then, we’re not a multicultural country. We’re just a monocultural country in brownface.”

— Daniel Chyi, Co-founder, Vidude.com

“Representation” Isn’t Always Revolution

More Māori and migrant faces in media and business is a step forward — but only if they’re not forced to perform Kiwi-palatable versions of themselves.

When diverse leaders are only platformed for their "relatable immigrant story", or when they become brand mascots for diversity, it strips their experience of its complexity and political reality.

A Samoan woman in Parliament isn’t representation if she can’t speak openly about racism in policy.

A Chinese Kiwi CEO isn’t progress if they’re not allowed to push back on anti-Asian sentiment in business culture.

The Price of “Respectability”

To gain mainstream acceptance, many migrants are encouraged to:

Stay out of activist spaces.

Distance themselves from other marginalised groups.

Downplay their heritage.

Adopt “neutral” — i.e., white — mannerisms, politics, and aesthetics.

This isn’t inclusion. It’s grooming. And it creates a dangerous narrative: that only “safe,” “grateful,” and apolitical migrants deserve a voice.

Meanwhile, those who challenge the system are labelled “divisive,” “angry,” or “ungrateful.”

Breaking the Illusion of Safety

More young people in Aotearoa — Māori, Pasifika, Asian, African, Middle Eastern — are rejecting the lie that success must come at the cost of identity.

They're telling stories on platforms like Vidude.com, where their creativity and commentary aren’t forced into corporate-friendly shapes. They’re building real communities, not just chasing followers. They’re refusing to be “white enough to be safe.”

Part 6: The “Immigrant Problem” Isn’t Immigration. It’s Our Narrative

Walk through talkback radio, scroll through online comment sections, or sit through a few local body meetings — and you’ll hear it.

“Too many migrants.”

“They don’t integrate.”

“They take our jobs, don’t learn the language, bring crime, change the culture.”

It’s an old tune with new variations — and it’s built not on reality, but on repetition.

Let’s be real: New Zealand doesn’t have an immigration problem. It has a storytelling problem.

The Myth of the Overcrowded Lifeboat

Politicians and media often frame Aotearoa like a lifeboat — just big enough for “real” Kiwis, but in danger of sinking under the weight of migrants.

This narrative is politically convenient. It distracts from:

Housing policy failures.

Underinvestment in health, education, and infrastructure.

Growing inequality between urban elites and everyone else.

It’s easier to blame newcomers than to challenge the powerful.

But immigration doesn’t break systems. It exposes the ones already broken.

Daniel Chyi on Narrative Responsibility:

“The people who tell the stories control the future. If we let fear shape how we talk about migration, we create enemies where there could be neighbours. At Vidude, we hand the mic to communities who’ve been silenced — not to echo fear, but to tell the whole truth.”

— Daniel Chyi, Co-founder, Vidude.com

Media Framing and the Bias We Inhale

Scan the headlines:

“Migrant crime wave.”

“Immigrants flooding the job market.”

“Foreign investors driving up house prices.”

Now look closer. These stories rarely mention:

White-collar tax fraud by locals.

How Kiwi landlords benefit from high migration.

Or how many migrants work two jobs just to survive.

We’ve created an ecosystem where migrants are visible only when blamed.

And that shapes public perception more than any fact sheet ever will.

Policy Is Storytelling With Consequences

The way we legislate migration — who gets in, who gets support, who gets deported — mirrors how we talk about migrants.

If your story is framed as:

A threat → you’ll get policed.

A burden → you’ll get blamed.

A guest → you’ll never be fully at home.

But if it’s framed as:

A contributor → you get protection.

A neighbour → you get investment.

A citizen → you get heard.

Changing our migration narrative isn’t just about PR. It’s about power.

Platforms Like Vidude: Rewriting the Script

Migrants and multicultural Kiwis are increasingly turning to community platforms like Vidude.com — because mainstream media has shown them time and again: they won’t be given the mic unless they fit a mould.

On Vidude:

Refugee youth are sharing unfiltered stories of arrival and resilience.

Migrant mums are documenting how they’re blending cultures — not erasing them.

Artists, comedians, gamers, and educators are saying: “This is also what being Kiwi looks like.”

It’s not about shouting louder. It’s about building new spaces where you’re not muted to begin with.

Part 7: Code-Switching for Survival — Migrants, Masks, and the Exhaustion of Belonging

Imagine walking into work each day with a version of yourself stripped for parts.

You greet everyone with a Kiwi accent — even though your mother tongue sings a different melody.

You laugh at jokes you don’t understand, and bite your tongue when someone mocks your culture.

You downplay your food, your faith, your family name.

This is code-switching — the everyday shapeshifting many migrants, especially people of colour, perform just to fit in.

And it’s bloody exhausting.

“Just Be Kiwi” — But What Does That Even Mean?

The pressure to "be Kiwi" is rarely defined outright, but it’s felt deeply.

It shows up when:

Your foreign qualifications are dismissed.

You’re told your name is too hard to pronounce.

You're praised only when your culture is made digestible for mainstream eyes — like a Diwali party at school, but no real curiosity about caste or colonialism.

Being “Kiwi enough” often means:

Whiteness-adjacent.

Accent-neutral.

Culturally inoffensive.

It's not multiculturalism. It's monoculturalism in drag.

Daniel Chyi on Identity and Survival:

“We’ve met creators on Vidude who literally publish two versions of every video — one for their community, one for the algorithm. That’s the cost of code-switching. We want to change that. One version. One voice. One future where you don’t have to split yourself in two to be seen.”

— Daniel Chyi, Co-founder, Vidude.com

Workplaces and the Mask of “Professionalism”

Ask any migrant who’s worked in corporate Aotearoa. The office can feel like a performance stage:

Suppress your accent.

Smile when your food is called “smelly.”

Avoid politics — especially if it involves your home country.

“Professionalism” is often code for assimilation — especially when managers say things like:

“We love diversity… as long as it doesn’t disrupt the vibe.”

“That’s interesting, but it’s not how we do things here.”

“Can you make that presentation more... Kiwi?”

What they mean is: shrink yourself.

Home Isn’t Safe Either

Even in migrant communities, code-switching happens.

Queer migrants hide their identities to avoid rejection.

Women navigate patriarchy and racism at the same time.

First-generation kids translate documents, dreams, and grief — often before they’re teenagers.

You’re not just switching between cultures — you’re balancing them on your back.

What Happens When You Turn the Mask Into the Brand?

Some migrants lean into the code-switch — because it's rewarded.

They become “diversity reps.”

They post cultural content that fits the Kiwi aesthetic: food, fashion, and folk dancing, but never systemic injustice.

They build social capital by erasing the parts of their culture that make others uncomfortable.

But eventually, the mask cracks. Because no one can live forever in a skin that isn’t theirs.

Vidude: A Place Where You Don’t Have to Translate Yourself

Platforms like Vidude.com offer an alternative — a home where:

You don’t need subtitles to be understood.

Your accent is part of your power, not a problem.

Your audience finds you — not the version you were forced to become.

We’re seeing creators build audiences who don’t expect them to shrink.

They don’t have to code-switch — they just get to code-create.

Part 8: Where’s the Real Support? Funding, Visibility, and the Gatekeeping of Culture in NZ

For all the warm, fuzzy talk about diversity and inclusion, here’s a hard truth:

In New Zealand, visibility is often granted only when it’s safe, sanitised, and palatable.

Especially for migrants and creatives of colour, the path to support is paved with gatekeepers who decide what counts as “authentic” — and what gets left on the cutting room floor.

Creative Grants: Who Gets the Purse Strings?

Let’s say you’re a new Kiwi artist, filmmaker, or educator from a migrant background.

You’re told:

“There’s plenty of funding available — just apply!”

But when you try:

The application is full of jargon not written for you.

The panel wants "a clear cultural hook” but not one that’s “too political.”

Your storytelling is “too niche” or “too risky” for mainstream platforms.

Meanwhile, projects that tick the same old Pākehā boxes get fast-tracked:

✅ Historical fiction set in Victorian-era NZ

✅ Beachy lifestyle vlog with trendy lingo

✅ “Global” stories that erase real ethnic complexity

The irony? Diversity is on the poster, but it’s not at the table.

Daniel Chyi on Funding and Gatekeeping:

“At Vidude, we see creators blocked not because they lack skill — but because they don’t have the right connections or polish for the funders’ idea of culture. That’s why we made the tools simple. No applications. No gatekeepers. Just a fair shot to be seen and paid.”

— Daniel Chyi, Co-founder, Vidude.com

Mainstream Media Still Picks the Narrative

Think about how many migrant voices are missing from:

Prime-time television

Major news outlets

National curriculum

NZ On Air-funded content

When migrants are featured, it’s often:

A feel-good story about food and family (never housing or hate crimes)

A single-day festival covered once a year

A surface-level interview with no follow-up

It’s not storytelling. It’s tokenism with better lighting.

Algorithms Are the New Colonisers

Even in the digital space, support isn’t equal.

Let’s say you’re a Pacific Island content creator who posts in your native language:

YouTube deprioritises you because of lower ad appeal.

Instagram shadowbans your hashtags for “low relevance.”

TikTok buries your post unless you hop on Western trends.

Visibility is coded into the algorithm.

And the algorithm wasn’t made for you.

Vidude Flips the Script for NZ Creators

Vidude doesn’t wait for cultural approval from a panel.

It gives:

Monetisation from day one — no need to hit viral thresholds.

Content control — so you don’t get demonetised for being you.

A Kiwi-first algorithm — boosting local voices, not burying them under American noise.

It’s not just a platform. It’s cultural independence in code.

Support Doesn’t Mean Saving — It Means Space

We don’t need:

More white-led diversity campaigns.

More "mentorship" from people who’ve never lived our lives.

More fake wokeness in policy documents.

We need:

Real resourcing.

Real equity.

Real ownership of our stories.

Vidude is built to offer exactly that.

Part 9: Teaching Aotearoa to Listen — How Migrants Are Educating, Not Just Entertaining

In mainstream Kiwi culture, migrant voices are often welcomed on one condition:

Be entertaining — not confronting.

You can bring your food, your dancing, your “colour,” your accent — as long as you don’t bring the truth.

But on platforms like Vidude, that tide is turning.

Migrant creators are using video to teach, challenge, and decolonise — not just perform.

From TikTok to Truth Bombs

We’ve all seen it:

A Samoan creator breaking down colonisation in 60 seconds.

A South Asian educator teaching Te Reo Māori to immigrants and Pākehā alike.

A Chinese Kiwi youth leader explaining systemic racism while flipping dumplings.

These aren't just influencers. They’re informal educators.

And they’re filling the gaps New Zealand schools, media, and politics keep leaving behind.

Daniel Chyi on Migrant Educators in NZ

“Some of the most powerful teachers in Aotearoa right now aren’t in classrooms. They’re online — creators breaking cycles with honesty, humour, and hustle. Vidude exists to give those voices a proper platform, not just a passing trend.”

— Daniel Chyi, Co-founder, Vidude.com

What Are They Teaching?

The topics many migrant creators cover would never make it past NZ On Air’s censors — or a polite PTA meeting:

How immigration policy still reflects colonial hierarchies

The double standards migrant women face around parenting and public space

The mental health toll of racism, intergenerational trauma, and hypervisibility

The forced assimilation of refugee youth in white-majority schools

Why “Kiwi values” often mask British ideals repackaged with a fern

They’re not trying to make the news.

They’re making knowledge go viral.

Why Platforms Matter

YouTube? You're competing with Logan Paul and 10 million mukbangs.

TikTok? You're one community guideline away from being banned.

Facebook? Your auntie loves it, but the kids are long gone.

Vidude gives NZ-based educators a platform designed around them.

Not ads. Not influencers. Not global clutter.

How Migrant Teachers Use Vidude:

Tutorials with local flavour: “How to navigate IRD as a new migrant” or “How to challenge casual racism at work”

Language lessons that cross cultures: Korean in Kaitaia, Hindi in Hawke’s Bay

Personal stories as curriculum: Immigration journeys, family history, identity crisis and reclamation

Workshops without walls: Upload once, teach forever — no Zoom fatigue, no algorithm drama

Whether it’s a quiet explainer or a firestarter manifesto, these videos reach, teach, and ripple.

A Platform That Doesn’t Censor Identity

The beauty of Vidude?

You don’t need to “tone it down” or “keep it neutral.”

No one’s going to demonetise you for:

Speaking your mother tongue

Naming your trauma

Quoting your ancestors

Calling out the Crown

Instead, Vidude says:

“You good, fam? Say what needs to be said.”

Kiwis Are Ready to Listen — But Not Through Gatekeepers

We’ve entered an era where:

Youth want authenticity, not filtered fragility.

Teachers are turning to creators for lesson resources.

Local governments are following content creators to understand communities they ignored.

In short: education isn’t happening in classrooms anymore — it’s happening in videos.

And when those videos come from migrants?

That’s not diversity.

That’s decolonial pedagogy with a GoPro.

Part 10: Culture, Code, and Community — What Aotearoa Could Be If We Actually Meant “Welcome”

In a nation that says “He waka eke noa” — we’re all in this canoe together — too many migrants are still asked to paddle quietly, sit at the back, or worse, jump off if their presence “rocks the boat.”

We celebrate multiculturalism on paper.

We praise diversity in marketing campaigns.

We make room for festivals and food stalls.

But when it comes to:

Migrant creators sharing their pain or pride?

Refugees challenging the colonial status quo?

Immigrants daring to educate instead of entertain?

Suddenly the silence creeps back in.

The Real Aotearoa Is Bigger Than the Tourism Brochure

We can’t call ourselves progressive while:

Expecting assimilation over celebration

Allowing migrant youth to drown in underfunded systems

Telling people to “be grateful” when they speak up about injustice

And we can’t pretend to be a “team of five million” when millions of lived realities are erased from public discourse, media representation, and political power.

Vidude Is Building a New Kind of Digital Marae

It’s not just a video platform.

It’s not just Kiwi tech.

It’s a wharenui for the unheard, unfiltered, and unapologetically local.

A place where:

Syrian teenagers can tell their migration story

Filipino nurses can document their burnout and brilliance

African youth can laugh, cry, and rage — and be met with respect, not suspicion

Māori, Pasifika, Asian, Pākehā and every culture can meet without erasure

No filters.

No algorithms suppressing real talk.

No pressure to “go viral” by being vanilla.

Just video with mana.

Daniel Chyi’s Final Word

“When we built Vidude, it wasn’t just for content — it was for connection. For every Kiwi who’s been told to tone it down, fade into the background, or just be grateful — this is your space. Aotearoa’s identity is still forming. Don’t let anyone write you out of it.”

— Daniel Chyi, Co-founder, Vidude.com

✅ Call to Action: Don’t Just Be Seen — Be Heard

If you’re:

A migrant creator sick of being boxed in by algorithms

An educator with a lesson only your community can teach

A young Kiwi trying to make sense of your identity and share it loud

🎥 Vidude.com is your platform.

Start your channel.

Tell your story.

Find your people.

Because Aotearoa doesn’t move forward with silence.

It moves forward with many voices — all speaking truth.