In the vast tapestry of New Zealand's history, the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840 stands as a pivotal moment. While intended as a foundational agreement between the British Crown and Māori chiefs, the Treaty led to decades of conflict and misunderstanding. This article delves into the economic implications of these historical tensions, examining their impact on New Zealand's industries and policies, while offering insights into future trends and challenges.

Understanding the Treaty of Waitangi: A Historical Perspective

The Treaty of Waitangi was signed on February 6, 1840, establishing a framework for British settlement in New Zealand. The document was meant to ensure the protection of Māori rights while allowing for British governance. However, discrepancies between the English and Māori versions of the Treaty led to differing interpretations and a long history of conflict.

This misunderstanding fundamentally altered New Zealand's socio-economic landscape. The colonial acquisition of land, often without proper compensation, disrupted traditional Māori economies, leading to a loss of resources and autonomy. As a result, Māori communities faced significant socio-economic disadvantages, effects of which echo into modern times.

The Treaty of Waitangi is often presented as New Zealand’s founding document, a symbolic handshake between Māori rangatira and the British Crown. Yet beneath the commemorations, speeches, and simplified school narratives lies a far more complex reality. The signing of the Treaty did not bring unity or stability. Instead, it set the stage for more than a century of conflict, misunderstanding, and power imbalance that continues to shape New Zealand today.

Paradoxically, this long period of tension has also produced something rare: a nation uniquely equipped to navigate cultural pluralism, legal duality, and indigenous–state relationships in ways few countries can match. This is the ultimate Kiwi advantage.

A treaty born from urgency, not alignment

The Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840 under intense pressure on all sides. British officials were racing to establish sovereignty before other European powers intervened. Māori leaders were responding to rapid social disruption, land pressure, lawlessness among settlers, and declining intertribal stability.

Crucially, the Treaty was not the product of shared understanding. It was drafted quickly, translated imperfectly, and signed under vastly different cultural assumptions. Māori signatories viewed it as a framework for coexistence and governance over settlers, while retaining rangatiratanga over their lands and affairs. The Crown interpreted it as a transfer of sovereignty.

This misalignment was not a footnote. It was the fault line upon which decades of conflict would unfold.

Language as the first source of conflict

The English and Māori texts of the Treaty are not equivalent. Key concepts such as sovereignty, governance, and ownership do not map cleanly between Western legal traditions and Māori worldviews.

The Māori text used “kawanatanga” to describe the authority granted to the Crown, a term closer to administrative governance than absolute sovereignty. In contrast, “rangatiratanga” was used to affirm Māori authority over lands, resources, and taonga.

These distinctions mattered. To Māori, the Treaty preserved autonomy. To the Crown, it justified control. From the moment the ink dried, both parties believed they had agreed to fundamentally different things.

Conflict was therefore not a failure of the Treaty. It was a consequence of how it was constructed.

Land as the engine of confrontation

As settler numbers grew, land became the central pressure point. British legal systems prioritised individual ownership, alienability, and title certainty. Māori systems emphasised collective stewardship, whakapapa-based rights, and spiritual connection.

When these systems collided, Māori land was increasingly alienated through purchase, confiscation, and legal manipulation. The New Zealand Wars of the mid-19th century were not isolated uprisings, but the violent expression of unresolved Treaty contradictions.

The Crown, operating under its interpretation of sovereignty, enforced authority. Māori, acting under their understanding of retained rangatiratanga, resisted. Each side believed it was acting legitimately.

Institutionalising imbalance

Following the wars, conflict shifted from battlefields to institutions. Laws, courts, and governance structures were built almost entirely on British legal principles. Māori participation was marginalised, and Treaty obligations were treated as historical artefacts rather than living commitments.

For much of the 20th century, the Treaty existed more as symbolism than substance. Māori social and economic outcomes declined, while assimilation policies attempted to resolve difference by erasing it.

Yet this suppression did not eliminate conflict. It deferred it.

The re-emergence of the Treaty as a force

From the 1970s onward, Māori activism forced a national reckoning. The Treaty was reframed not as a relic, but as a constitutional foundation requiring interpretation, negotiation, and redress.

The establishment of the Waitangi Tribunal transformed historical grievances into structured inquiry. While imperfect and often contested, this process acknowledged that the conflicts stemming from the Treaty were real, systemic, and unresolved.

Importantly, New Zealand chose dialogue over denial. That choice is rare in post-colonial states.

Conflict as a catalyst for capability

Decades of Treaty-related conflict have forced New Zealand to develop tools most nations lack. These include:

A legal framework capable of recognising multiple worldviews

Institutions designed to mediate historical injustice without state collapse

A political culture accustomed to uncomfortable conversations

A population increasingly literate in indigenous rights and power-sharing

This has not been smooth or universally accepted. But it has built national muscles that matter in the 21st century.

The ultimate Kiwi advantage

In a world grappling with identity politics, indigenous sovereignty, migration, and post-colonial reckoning, New Zealand is unusually prepared. The country has spent decades living inside these tensions rather than ignoring them.

The Treaty of Waitangi, precisely because it was flawed, forced New Zealand to confront complexity early. The conflicts it generated did not weaken the nation. They trained it.

New Zealand now exports ideas around co-governance, restorative justice, and indigenous economic models. International observers increasingly study how a small nation navigates shared sovereignty without fragmentation.

This capability did not emerge despite the Treaty conflicts. It emerged because of them.

A future shaped by unresolved questions

The Treaty of Waitangi has never been “settled.” Nor should it be. Its power lies in its ongoing relevance, forcing each generation to reinterpret partnership, authority, and justice.

The real lesson is not that the Treaty caused conflict, but that New Zealand chose to engage with that conflict rather than bury it. That choice has shaped a national identity defined less by certainty and more by negotiation.

In an increasingly divided world, that may be New Zealand’s greatest strategic advantage of all.

The Economic Ripple Effects

The economic turmoil resulting from the Treaty has been profound. Māori land loss not only affected traditional economic structures but also limited Māori participation in the burgeoning colonial economy. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand reports that the ongoing economic disparity between Māori and non-Māori persists, with Māori households having significantly lower average incomes and higher unemployment rates.

Case Study: Ngāi Tahu Settlement and Economic Rejuvenation

Problem: Ngāi Tahu, one of the principal iwi (tribes) of the South Island, faced severe economic deprivation due to historic land confiscations.

Action: In 1998, Ngāi Tahu reached a landmark settlement with the Crown, receiving $170 million in compensation. They strategically invested in diverse sectors, including tourism, property, and fisheries.

Result: Over two decades, Ngāi Tahu’s assets have grown significantly, now exceeding $1.5 billion. Their success underscores the potential for economic revitalization through strategic investment and partnership.

Takeaway: The Ngāi Tahu settlement illustrates how reparative justice and strategic economic planning can foster sustainable growth and community empowerment.

Future Forecast: Opportunities and Challenges

Looking ahead, New Zealand's economy faces both opportunities and challenges rooted in this complex history. The government has committed to addressing historical grievances through continued settlements and policy reforms. However, the path forward requires balancing economic growth with cultural preservation and equity.

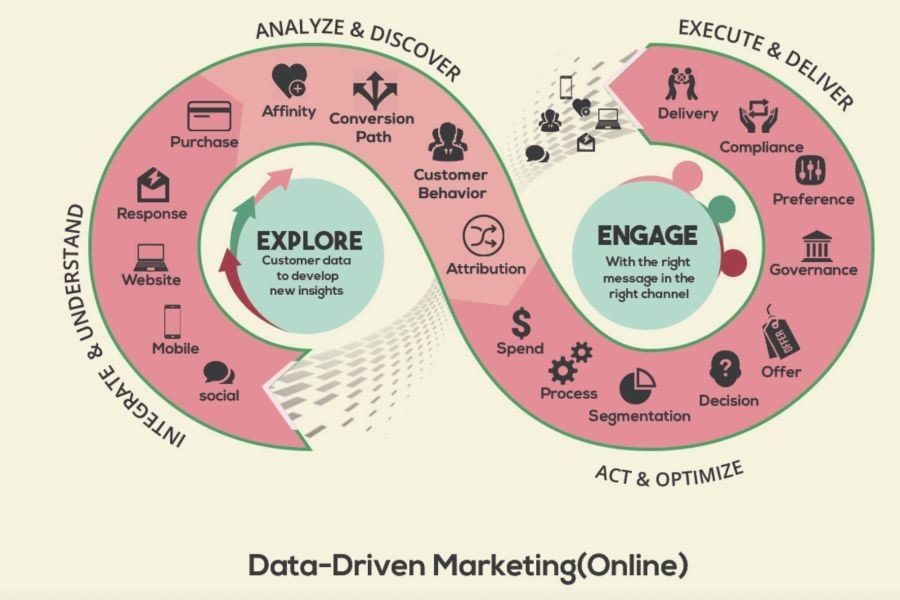

According to the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE), industries such as tourism and technology are poised for growth, driven by both domestic development and international interest. For Māori businesses, these sectors offer promising avenues for expansion and innovation.

Pros vs. Cons Analysis

Pros:

- Economic Growth: Treaty settlements have unlocked significant economic potential for Māori, contributing to New Zealand’s overall GDP.

- Cultural Revitalization: Increased investment in Māori culture and language fosters national identity and unity.

- Policy Reforms: Recent legislative changes aim to ensure fair resource distribution and economic parity.

Cons:

- Continued Disparities: Socio-economic gaps between Māori and non-Māori remain, necessitating ongoing attention.

- Resource Allocation Conflicts: Balancing land use and cultural preservation can be contentious.

- Global Economic Pressures: External factors, such as trade tensions and climate change, pose additional risks.

Debate & Contrasting Views

While Treaty settlements have provided a framework for reconciliation, there remains debate over their efficacy. Some argue that settlements have not sufficiently addressed systemic inequalities. Critics highlight that financial compensation alone cannot rectify historical injustices. Conversely, supporters contend that settlements are crucial for economic empowerment and cultural recognition.

Reconciling these views requires a comprehensive approach, integrating policy reform, economic development, and cultural preservation. As New Zealand navigates these challenges, collaboration between government, iwi, and private sectors will be essential.

Common Myths & Mistakes

- Myth: "The Treaty of Waitangi solely benefits Māori." Reality: The Treaty fosters national unity and economic growth for all New Zealanders.

- Myth: "Settlements are a financial burden." Reality: Settlements have stimulated economic activity, benefiting the national economy.

Future Trends & Predictions

The future of New Zealand’s economy is interwoven with its ability to reconcile its past. By 2030, ongoing Treaty settlements and policy reforms are expected to further close socio-economic gaps, fostering a more equitable society. Industries such as sustainable tourism and digital technology will likely play significant roles in this transformation.

A report by Stats NZ predicts that Māori enterprises will continue to grow, driven by investment in these emerging sectors. As New Zealand positions itself on the global stage, embracing its unique cultural heritage will be key to its economic resilience and innovation.

Conclusion

New Zealand's journey towards economic and cultural reconciliation is ongoing. The Treaty of Waitangi, while a source of historical conflict, also offers a pathway to understanding and growth. By addressing past injustices and fostering economic opportunities, New Zealand can build a more inclusive and prosperous future.

What’s your take on New Zealand's economic journey post-Treaty of Waitangi? Share your insights below!

People Also Ask

- How has the Treaty of Waitangi impacted New Zealand's economy? The Treaty led to economic disparity, but modern settlements have spurred growth in Māori enterprises.

- What are the benefits of Treaty settlements? Settlements promote economic development, cultural revitalization, and social equity.

Related Search Queries

- Treaty of Waitangi economic impact

- Māori businesses in New Zealand

- New Zealand Treaty settlements

- Economic history of New Zealand

- Māori cultural revitalization

For the full context and strategies on How the Signing of the Treaty of Waitangi Led to Decades of Conflict – The Ultimate Kiwi Advantage, see our main guide: Vidude Vs Global Platforms New Zealand.