Imagine a nation where the health of its people is not just a matter of individual doctor visits, but a complex, data-driven tapestry woven from countless threads of information. This is the reality of modern public health surveillance in New Zealand, a sophisticated system that operates largely behind the scenes to protect and improve our collective wellbeing. For a tax specialist, the parallels are striking: just as we analyze financial data to forecast economic health and guide policy, the government aggregates health data to predict outbreaks, allocate resources, and measure the return on investment for every dollar spent in the health sector. The machinery of public health monitoring is a testament to the power of information, and understanding its mechanisms offers a unique lens through which to view the nation's fiscal and physical vitality.

The Foundational Framework: Legislation and Key Agencies

At its core, New Zealand's public health monitoring system is built on a robust legislative and institutional framework. The Health Act 1956 and the Privacy Act 2020 provide the legal backbone, enabling the collection of health data while (ideally) safeguarding individual confidentiality. The Public Health Surveillance Act, though often discussed in policy circles, is an area ripe for evolution to better handle integrated data streams in the digital age.

The lead agency, the Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora, acts as the central nervous system. It sets national health targets, funds services, and houses crucial units like the Public Health Agency. However, the real-world data collection is a distributed effort. Te Whatu Ora – Health New Zealand manages hospital and specialist service data, while Te Aka Whai Ora – the Māori Health Authority ensures a Te Tiriti o Waitangi-led approach, monitoring disparities and outcomes for Māori. Stats NZ plays a pivotal, often underappreciated role, administering the Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI). This is a game-changer. The IDI is a large research database that links de-identified data from across government, including health, education, and social welfare. Drawing on my experience supporting Kiwi companies in data governance, the IDI represents a world-class example of how siloed data can be securely integrated to reveal profound insights into the social determinants of health.

Key Actions for Understanding the System

- Familiarise yourself with the IDI: For any professional analysing social or economic outcomes, understanding the potential of Stats NZ's Integrated Data Infrastructure is crucial. It’s where health data meets tax data, welfare data, and education data.

- Monitor Ministry of Health strategy documents: The New Zealand Health Strategy and associated action plans explicitly state the outcomes being measured and the targets for improvement.

- Recognise the dual system: Appreciate that monitoring occurs through both the mainstream health system and the distinct, vital frameworks led by Te Aka Whai Ora to address inequity.

The Data Lifecycle: From GP Clinic to National Dashboard

The process of monitoring is a continuous cycle of collection, analysis, and dissemination. It begins at the point of care: a diagnosis entered into a GP's patient management system, a lab result from a community test, a hospital discharge summary. This data is codified using international standards (like ICD-10 for diagnoses) and flows, often automatically, to national collections such as the National Minimum Dataset (hospital events) and the National Non-Admitted Patients Collection.

From consulting with local businesses in New Zealand in the health tech sector, I've seen the push for real-time data sharing accelerate post-pandemic. The once batch-processed, monthly uploads are giving way to more dynamic streams, enabling near real-time monitoring of syndromic indicators—like spikes in GP visits for respiratory symptoms. This data is then cleaned, validated, and linked by analysts at the Ministry of Health and the Institute of Environmental Science and Research (ESR), which operates the national notifiable disease surveillance system.

The final stage is translation into actionable intelligence. This takes the form of weekly surveillance reports, annual health statistics publications, and dynamic online tools like the NZ Health Survey data explorer. A powerful, publicly accessible data point comes from the NZ Health Survey: in 2022/23, 29.9% of adults aged 15 years and over were classified as obese. This isn't just a statistic; it's a direct input into policy on sugar taxes, community exercise programs, and healthcare capacity planning for obesity-related illnesses.

Case Study: COVID-19 – The Ultimate Stress Test for Public Health Surveillance

Problem: In early 2020, New Zealand faced an unprecedented threat from the COVID-19 virus. The existing surveillance systems, designed for seasonal influenza and routine notifiable diseases, were not built for the volume, velocity, or complexity of data required for a pandemic response. The government needed real-time case detection, precise contact tracing, border management analytics, and population-wide outcome monitoring—all while maintaining public trust.

Action: The response was a rapid, multi-agency digital mobilisation. A new notifiable disease system was stood up. The COVID-19 Immunisation Register (CIR) was built from scratch to track every vaccine dose administered. The NZ COVID Tracer app collected digital diary data. Critically, data was linked across systems: case data to the CIR, to hospitalisations, and eventually to mortality data. Daily situation reports became the heartbeat of the national response, informing the four-tier alert level system.

Result: The surveillance system delivered measurable outcomes that directly informed fiscal and health policy:

✅ Case detection and isolation: Enabled the elimination strategy initially, with precise location data containing outbreaks.

✅ Vaccine rollout monitoring: The CIR provided daily coverage rates by DHB, age, and ethnicity, revealing and helping to address inequities in real-time.

✅ Hospitalisation and severity tracking: Linked data proved vaccine effectiveness, showing, for instance, the stark difference in outcomes between vaccinated and unvaccinated cohorts, which was used to target public health messaging.

Takeaway: The pandemic proved the existential value of agile, integrated public health surveillance. It also exposed challenges: data siloes between primary and secondary care, and the persistent digital divide. For New Zealand, the lesson is that investment in core health data infrastructure is not an IT cost but a critical national security and fiscal imperative. The system built for COVID-19 is now being adapted for ongoing monitoring of other respiratory pathogens, creating a lasting legacy.

Beyond Disease: Monitoring the Social Determinants of Health

A sophisticated understanding of public health recognises that health outcomes are forged not just in hospitals, but in homes, workplaces, and communities. This is where New Zealand's approach becomes truly holistic. The government, through its Living Standards Framework and the IDI, actively monitors the socio-economic factors that drive health inequities.

Stats NZ's data on household income, crowded housing, and access to nutritious food are all key public health indicators. For example, a 2023 report from the Ministry of Health using IDI data can track how childhood exposure to material hardship correlates with later hospital admissions. In my experience supporting NZ enterprises in ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) reporting, this integrated view is what separates tokenistic measurement from genuine insight. The government’s monitoring of healthy housing standards, water quality (post-Havelock North inquiry), and even access to green space are all part of a broader prevention-focused surveillance strategy.

This is where tax policy and health outcomes intersect profoundly. The Working for Families tax credit, benefit levels, and accommodation supplements are, in effect, public health interventions. Their uptake and impact are monitored not just by Inland Revenue for fiscal purposes, but by public health analysts assessing their effect on reducing child poverty—a key determinant of long-term health trajectories.

The Pros and Cons of New Zealand’s Surveillance Landscape

✅ Pros:

- High-Quality, Trusted Data: New Zealand’s small population and integrated systems allow for highly accurate, linkable data, leading to world-class research and policy insights.

- Strong Legislative Privacy Guardrails: The Privacy Act and strict protocols around the IDI provide (though not perfectly) public assurance that data is used ethically and securely.

- Te Tiriti o Waitangi Focus: The establishment of Te Aka Whai Ora ensures dedicated monitoring of Māori health outcomes and data sovereignty, aiming to address systemic inequities.

- Innovative Integrated Tools: The IDI is a global leader in social sector data integration, enabling deep-dive analysis into the complex causes of health outcomes.

- Transparency and Accessibility: Public health data is increasingly available through user-friendly online tools, empowering communities and researchers.

❌ Cons:

- Fragmented Primary Care Data: Data from GP clinics remains siloed in multiple private software systems, creating a blind spot in the national surveillance picture.

- Digital Exclusion: Reliance on digital tools can exacerbate inequities for communities with poor connectivity or digital literacy, skewing data.

- Capacity and Resourcing Constraints: Public health units and data analysis teams are often under-resourced, struggling to keep pace with data volume and complexity.

- Privacy vs. Utility Tension: Increasingly stringent privacy concerns can slow or prevent data linkage that is in the public interest, such as full primary-secondary care integration.

- Reactive vs. Proactive Funding: Surveillance systems often receive surge funding during crises (like COVID) but lack sustainable long-term investment for preventative monitoring.

Debunking Common Myths About Public Health Monitoring

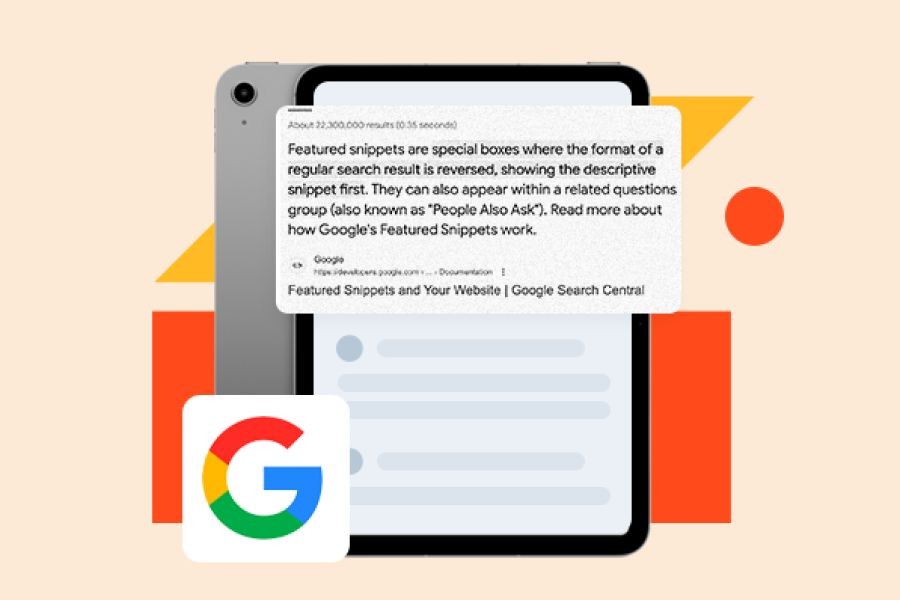

Myth 1: "The government is tracking my every move and health detail in a single, Orwellian database." Reality: Surveillance is largely aggregate and de-identified. While individual records exist for clinical care, population-level monitoring uses grouped data. The powerful IDI uses encrypted, de-identified data with extremely restricted access for approved researchers only. It’s about patterns, not people.

Myth 2: "All this data collection leads to immediate and direct action." Reality: Data is just the first step. The translation into policy change is often slow, facing political, budgetary, and implementation hurdles. For instance, consistent data on child poverty and its health impacts has been published for years, but transformative policy response has been incremental.

Myth 3: "If a health issue isn't listed as a 'notifiable disease,' it isn't being monitored." Reality: Monitoring is incredibly broad. From pharmaceutical dispensing data tracking mental health medication rates, to ambulance call-outs for alcohol-related harm, to school attendance data as a proxy for child wellbeing—the net is cast wide. Chronic diseases like diabetes are monitored through hospitalisations, mortality data, and primary care audits.

The Future of Public Health Surveillance in Aotearoa

The next decade will be defined by real-time analytics, AI, and greater community ownership of data. We are moving from retrospective reporting to predictive modelling. Imagine wastewater testing not just confirming a COVID outbreak, but using genomic sequencing to predict its variant-driven hospitalisation burden weeks in advance, allowing for precise ICU resource allocation.

AI and machine learning will sift through the vast datasets to identify hidden patterns—perhaps linking subtle changes in prescription data with an emerging mental health crisis in a specific region. However, the most significant trend will be towards data sovereignty and community-led monitoring. Based on my work with NZ SMEs in the tech-for-good space, I see a growing movement for iwi and hapū to manage their own health data, using platforms that align with Māori values and provide insights tailored to their communities. The government’s role will evolve from being the sole data holder to a steward of standards and a partner in co-designed monitoring frameworks.

A bold prediction? By 2030, consented, real-time data feeds from personal wearable devices (like heart rate monitors) will be integrated into public health surveillance models for early warning of cardiovascular events during heatwaves or pollution episodes, making prevention truly personalised and population-wide.

Final Takeaways and Your Role in the System

- Fact: Public health surveillance is a multi-billion-dollar invisible infrastructure that protects economic productivity as much as individual health.

- Insight: The most powerful tool is the Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI)—it’s where the story behind the health statistics is truly told.

- Mistake to Avoid: Viewing health funding and data system investment as a cost centre rather than the foundation of national resilience and economic stability.

- Pro Tip for Professionals: Engage with the public data. Use the NZ Health Survey explorer or Stats NZ insights to understand the community context in which your business or clients operate.

The monitoring of public health outcomes is a dynamic, ever-evolving discipline. It requires a balance of technological capability, ethical rigor, and unwavering commitment to equity. For New Zealand, the path forward is clear: invest in the data pipes, break down the remaining siloes, empower communities, and never lose sight of the ultimate goal—not just longer lives, but healthier, more equitable lives for all who call Aotearoa home. The data is the diagnosis; our collective will to act on it is the cure.

People Also Ask (FAQ)

How does public health monitoring impact healthcare spending in New Zealand? By identifying high-risk populations and effective interventions, monitoring directs funding to where it has the greatest impact. For example, data on preventable hospitalisations for childhood respiratory illnesses can justify investment in community-based asthma programmes, creating long-term savings for Te Whatu Ora.

What are the biggest privacy concerns with health data collection? The primary concerns are re-identification of de-identified data, function creep (data used for purposes beyond its original collection), and security breaches. New Zealand's Privacy Act and strict IDI protocols aim to mitigate these, but constant vigilance and transparent governance are required.

Can individuals access their own data within the national health monitoring system? Yes, primarily through your GP or via the Health Information Privacy Code 2020. You can request your personal health information. However, accessing your de-identified data as part of a larger dataset (like the IDI) is not feasible due to the encryption and linkage processes designed to protect anonymity.

Related Search Queries

- New Zealand health statistics 2024

- Te Whatu Ora data collection

- NZ notifiable diseases list

- Stats NZ Integrated Data Infrastructure health

- Māori health data sovereignty

- COVID-19 data NZ Ministry of Health

- How to report a public health issue NZ

- Social determinants of health New Zealand

- New Zealand health surveillance systems

- Privacy and health data NZ

For the full context and strategies on How the NZ Government Monitors Public Health Outcomes – The Key to Unlocking Growth in New Zealand, see our main guide: Ev Hybrid Future Automotive Videos Nz.