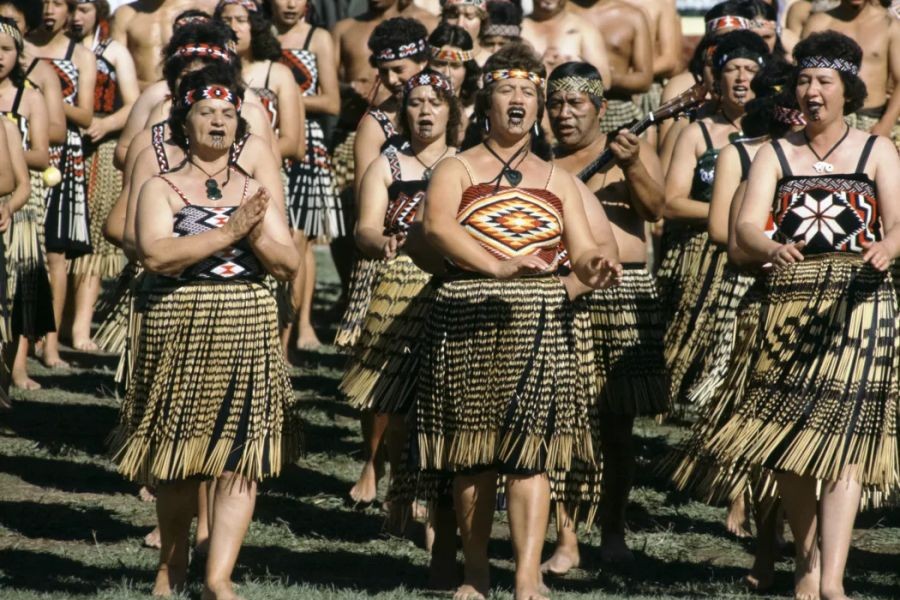

From the outside, New Zealand projects an image of a progressive utopia—a land of bold climate action, social equity, and innovative governance. This brand is a powerful export, attracting talent and investment. Yet, from the vantage point of a technology strategist, this narrative often obscures a more complex and less flattering reality. The gap between progressive branding and technological execution is not merely an oversight; it is a systemic vulnerability that threatens New Zealand's long-term economic sovereignty and competitive edge. While the government champions digital transformation, its foundational policies frequently lack the architectural rigor, data-centricity, and ruthless prioritization required to turn ambition into scalable, future-proof systems. This analysis will dissect the mechanics of this disconnect, evaluate its tangible costs, and propose a strategic recalibration essential for a nation that cannot afford to coast on reputation alone.

How It Works: The Architecture of the "Progressive" Disconnect

The core issue is not a lack of progressive intent, but a flawed implementation model. New Zealand's approach often prioritizes political signalling and consensus-building over the hard disciplines of systems engineering and outcome-based investment. This creates a chasm between policy announcement and technological reality.

The Consensus-Driven Model vs. Strategic Imperative

New Zealand's small, interconnected society naturally favors consensus. However, when applied to complex technological strategy, this can dilute decisive action. Initiatives become broad, inclusive, and politically palatable, but lack the sharp focus needed to solve specific, high-impact problems. For instance, the goal of a "digital economy" is universally endorsed, but the difficult trade-offs—such as prioritizing foundational digital infrastructure over a myriad of smaller, feel-good pilot projects—are often avoided. This results in a scattered portfolio of digital initiatives rather than a coherent, stackable technology architecture for the nation.

Data Deficit in Decision-Making

True progressivism in the 21st century is data-driven. Yet, critical policy decisions are frequently made with alarming gaps in real-time data or rigorous modelling. Consider housing: a perennial crisis addressed with a suite of policies. However, without a fully integrated, national-scale data fabric tracking housing stock, materials supply chains, consenting workflows, and workforce mobility in real-time, interventions are inherently blunt instruments. The 2023 New Zealand Productivity Commission report explicitly highlighted that poor data availability and use is a major barrier to improving housing affordability and productivity. This isn't a minor gap; it's a fundamental failure to build the informational nervous system required for modern governance.

The Innovation Theatre Complex

A tangible manifestation of this disconnect is what strategists term "innovation theatre." New Zealand excels at creating innovation hubs, startup grants, and tech festivals. These are valuable for ecosystem building. However, they often exist in parallel to, rather than integrated with, the country's major economic engines. The most telling data point: despite a vibrant startup scene, business investment in research and development (R&D) as a percentage of GDP remains stubbornly low compared to OECD peers. According to Stats NZ, business expenditure on R&D was 0.65% of GDP in 2022. This suggests a failure to translate progressive innovation rhetoric into deep, risk-taking capital investment at the core of industry.

Pros & Cons Evaluation: The Strategic Balance Sheet

✅ The Advantages of the Progressive Brand

- Global Talent Attraction: The "clean, green, progressive" brand is a powerful magnet for skilled immigrants, particularly in tech sectors, helping to offset brain drain.

- Social License for Experimentation: Public trust, while fragile, is generally higher than in many nations, allowing for piloting novel approaches like digital identity or algorithmic transparency in government services.

- Early Adopter Potential: Small scale and connected communities can, in theory, allow for rapid testing and iteration of new technologies, from renewable energy grids to precision agriculture.

- ESG Alignment: The national brand aligns perfectly with global Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) investment criteria, potentially directing capital towards sustainable infrastructure projects.

❌ The Strategic Costs and Vulnerabilities

- Complacency Risk: The strength of the brand can breed complacency, masking underlying stagnation in productivity and technological adoption. It allows "doing okay" to feel like "leading the world."

- Misallocation of Capital: Funding flows towards initiatives that reinforce the brand (e.g., symbolic climate projects) rather than towards unsexy, critical infrastructure like national fibre backbone resilience or modernising legacy core government IT systems.

- Slow Pace of Execution: The consensus model, while inclusive, is often anathema to the speed required in tech. Competitor nations with more centralised, decisive models can outpace New Zealand in deploying critical technologies.

- Superficial Metrics: Success is often measured in announcements and participation rates, not in hard outcomes like productivity lift, export diversification, or reduction in the digital divide. The focus is on input, not output.

Comparative Analysis: New Zealand vs. The Strategic Playbook

Contrast New Zealand's approach with that of a nation executing a deliberate, technology-first strategy. Estonia is the canonical example. Post-Soviet independence, it faced a blank slate and existential threats. Its response was not merely progressive politics; it was a constitutional-level commitment to digital infrastructure.

- Architectural Foundation: Estonia built X-Road, a mandatory, secure data exchange layer for all government and private sector services. New Zealand has multiple, often incompatible, data systems.

- Citizen as User: Estonia treats citizens as users of a state platform, with digital identity (e-ID) as the single sign-on. New Zealand's approach to digital identity has been fragmented and optional.

- Ruthless Prioritisation: Estonia's small size forced extreme prioritisation on digital sovereignty and efficiency. New Zealand's relative comfort has allowed for a more diffuse set of priorities.

The lesson is not that New Zealand should become Estonia. The lesson is that true progressive advantage in the digital age is won not by sentiment, but by superior system architecture. New Zealand's strategy often resembles a collection of well-intentioned apps built on shaky, legacy foundations.

Case Study: The New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme (NZ ETS) – A System Struggling with Scale

Problem: The NZ ETS is a cornerstone of New Zealand's progressive climate branding, designed to put a price on carbon and drive emissions reductions. However, as a market-based mechanism, its effectiveness is entirely dependent on the integrity, transparency, and real-time functionality of its underlying registry and trading platform. The system has faced persistent criticism for complexity, lack of transparency for smaller participants, and vulnerability to market manipulation due to data lags and limited auditability. For a tool meant to drive a fundamental economic transformation, its technological execution has been lacking.

Action: The government, through the Environmental Protection Authority (EPA), has undertaken a multi-year program to modernize the NZ ETS registry. This involves migrating to a more robust digital platform intended to improve user experience, data accessibility, and system security. The action acknowledges that the policy's credibility hinges on its digital plumbing.

Result: The transition has been rocky, highlighting the difficulty of modernizing critical national systems. Users have reported delays, usability issues, and a steep learning curve. While the long-term goal is a more secure and efficient system, the short-term result has been operational friction for businesses complying with the scheme. This undermines confidence in the market and, by extension, the policy itself. The measurable outcome is not just technical performance, but a loss of trust in a key progressive policy instrument.

Takeaway: This case study demonstrates that even the most progressive policy is only as strong as the technology platform that enacts it. For New Zealand, the challenge is systemic: too often, grand policy is launched without a concurrent, military-grade commitment to building the unglamorous, scalable digital infrastructure required for its success. The NZ ETS experience should serve as a cautionary tale for other flagship initiatives, from the Social Investment Agency's data-driven welfare approach to the reform of the Resource Management Act.

Common Myths & Mistakes in Assessing NZ's Progressive Stance

Myth 1: "New Zealand is a world leader in digital government." Reality: While certain services are praised, New Zealand ranks 13th in the UN's 2022 E-Government Development Index, behind regional peers like South Korea, Singapore, and Australia. Leadership is sporadic, not systemic, often held back by legacy systems and siloed agency approaches.

Myth 2: "Progressive values automatically translate to innovative economies." Reality: Values set direction, but execution builds economies. New Zealand's high-level commitment to well-being and sustainability has not yet catalyzed a proportional surge in deep-tech R&D or productivity growth, which remains a persistent weakness according to the Productivity Commission.

Myth 3: "Being small and agile gives NZ a tech advantage." Reality: Small size can enable speed, but only with decisive leadership and concentrated resources. More often, small size leads to risk aversion, capacity constraints, and a tendency to adopt overseas tech solutions rather than build sovereign capability.

The Controversial Take: New Zealand's "Progressivism" is a Strategic Distraction

Here is the contrarian, strategic perspective: New Zealand's focus on its progressive brand has become a dangerous distraction from the urgent, non-ideological task of national technological resilience. While the public debate is consumed with fine-tuning climate targets or social policy nuances, the foundational platforms of the nation—its energy grid, telecommunications infrastructure, financial systems, and core government services—are undergoing a slow-motion crisis of modernisation.

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand has repeatedly warned about the cyber vulnerability of the financial system. The 2021 Waikato DHB ransomware attack was a stark demonstration of critical infrastructure fragility. These are not progressive or conservative issues; they are strategic imperatives. The relentless focus on the former can drain oxygen and capital from the latter. A nation that cannot secure its digital borders or guarantee the continuity of its critical services has no platform from which to project any kind of values, progressive or otherwise. The priority must shift from branding to engineering.

Future Trends & Predictions: The Reckoning Ahead

The next decade will force a reckoning. The trends are clear:

- Sovereign AI & Data: Global fragmentation will demand sovereign control over data and AI models. New Zealand's current ad-hoc, cloud-dependent approach will be exposed as a strategic vulnerability. By 2030, either a coherent national data strategy with sovereign compute infrastructure will exist, or NZ's economy will be a rule-taker in the digital sphere.

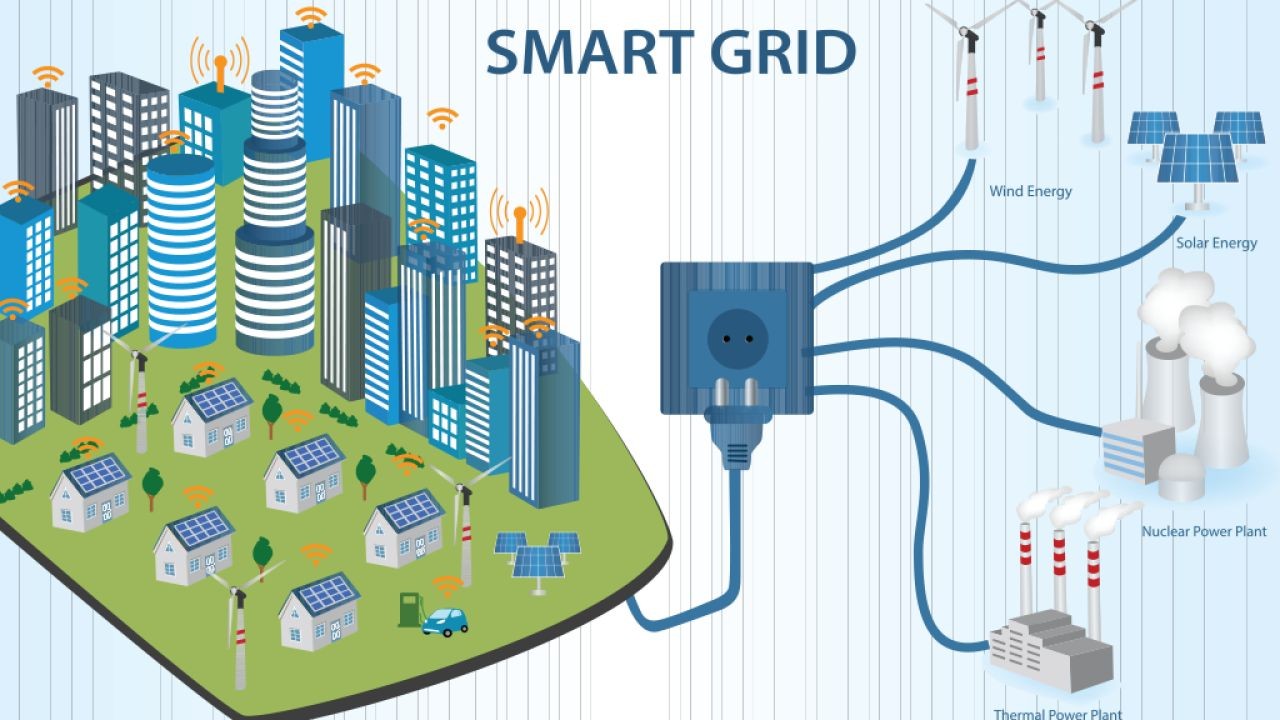

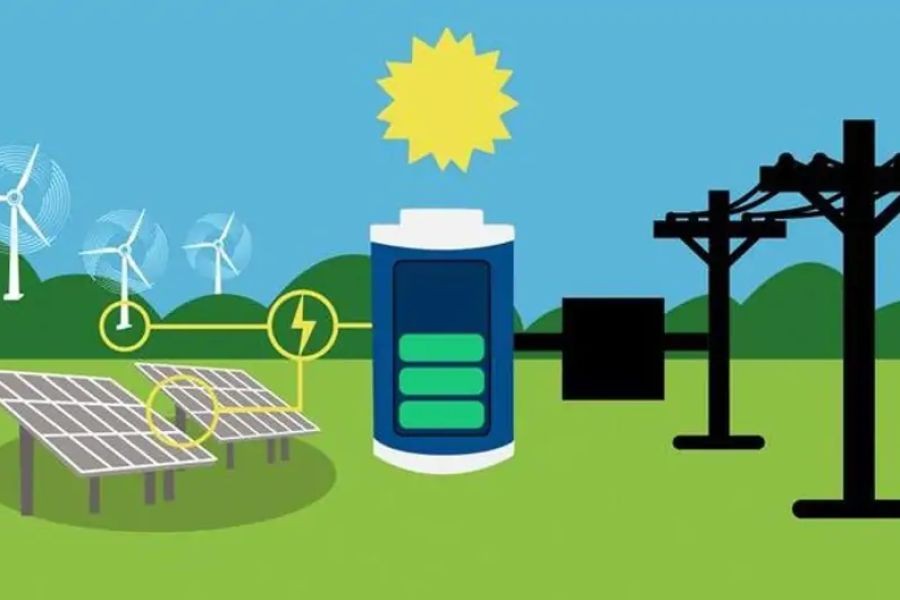

- Climate-Driven Tech Mandates: Meeting climate commitments will be impossible without radical technology adoption in primary industries and energy. This will move from voluntary "green tech" to mandatory operational overhauls, straining the capacity of the economy.

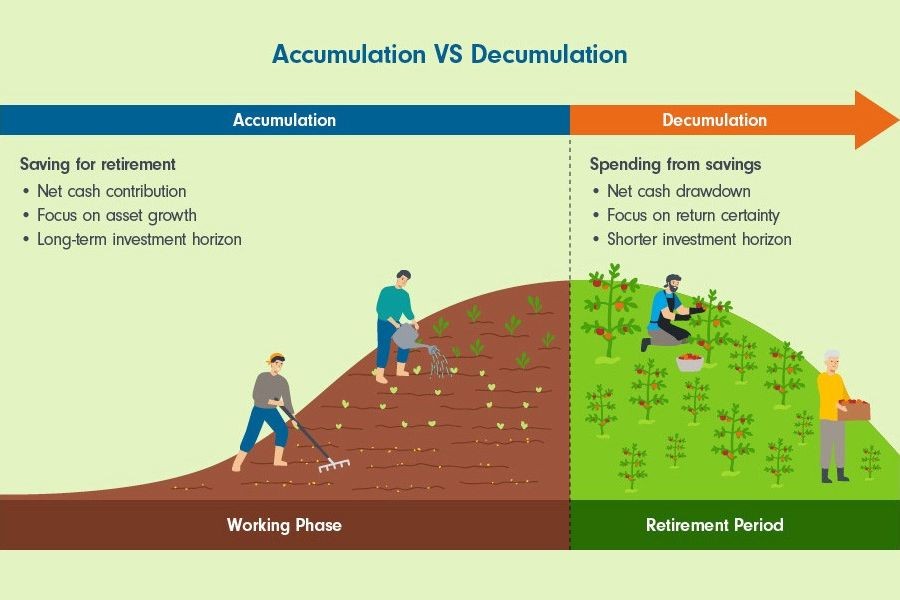

- The Productivity Imperative: An aging population will make productivity growth through technology not an option, but an existential requirement for maintaining living standards. The MBIE's own forecasts highlight this demographic pressure.

The prediction is this: by 2030, New Zealand will have been forced to abandon "innovation theatre" and make brutal, focused investments in a handful of foundational technology platforms (e.g., a national data exchange, a sovereign cloud for critical services, an integrated energy grid management system) or face significant economic decline relative to peers who did.

Final Takeaways & Call to Action

For the technology strategist, the analysis leads to a clear set of conclusions:

- Architecture Over Announcements: Scrutinize the underlying system design of any progressive policy. If it lacks a clear, scalable, and secure technology architecture, it is merely rhetoric.

- Invest in Foundations, Not Façades: Advocate for capital allocation towards the unsexy, critical infrastructure that enables everything else—data interoperability, security resilience, and modern core systems.

- Measure Outputs, Not Intentions: Demand hard metrics: productivity gains, export growth in tech services, reduction in system outages, time-to-value for digital projects.

- Embrace Decisive Engineering: Accept that technological sovereignty requires difficult, non-consensus decisions about standards, platforms, and priorities. Speed and coherence must sometimes trump perfect inclusivity.

New Zealand's progressive aspirations are not the problem; they are a potential source of direction. The problem is the lack of engineering-grade discipline to turn them into a durable competitive advantage. The call to action is for a strategic shift from being a narrator of progressive values to becoming an architect of a resilient, technologically sovereign future. The world is littered with nations that had a good story to tell but lacked the systems to sustain it. The question for New Zealand is: which side of that history will it be on?

What’s your take? Does New Zealand’s progressive brand accelerate or hinder its technological future? Share your analysis below.

People Also Ask (FAQ)

How does New Zealand's "progressive" policy environment actually impact tech investment? It creates a double-edged sword. The brand attracts ESG-focused capital and talent, providing a positive initial signal. However, investors quickly look past the brand to execution capability, regulatory clarity, and infrastructure. Persistent gaps in digital infrastructure, R&D commercialisation, and tech talent density can ultimately deter deep-tech investment despite the progressive backdrop.

What is the single biggest technological risk to New Zealand's economy? Strategic complacency born from an over-reliance on its positive international brand. The risk is not a specific technology, but the failure to make the concentrated, long-term investments in sovereign digital infrastructure (data, compute, security) needed to maintain economic self-determination in a fragmented world.

Can New Zealand realistically build sovereign tech capability at its scale? Yes, but not in all domains. The strategy must be ruthlessly focused. It should involve building sovereign control over critical national data assets and core government platforms, while strategically partnering in other areas. The goal is not autarky, but ensuring control over the systems that define national sovereignty in the 21st century.

Related Search Queries

- New Zealand digital economy strategy 2024

- NZ tech productivity gap

- Estonia vs New Zealand digital government

- New Zealand sovereign cloud strategy

- NZ Emissions Trading Scheme technology problems

- New Zealand R&D investment statistics

- Cybersecurity risks to New Zealand infrastructure

- Future of work NZ technology impact

- New Zealand data sovereignty law

- Public sector digital transformation NZ case studies

For the full context and strategies on The Truth About New Zealand’s So-Called ‘Progressive’ Politics – Everything You Need to Know as a Kiwi, see our main guide: Nz Cultural Future Arts Videos.